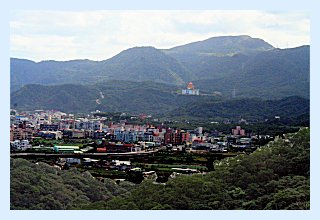

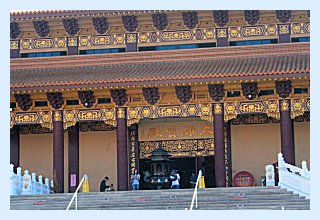

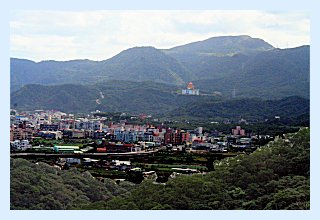

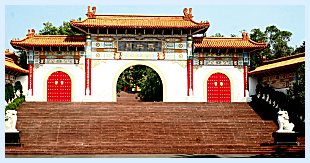

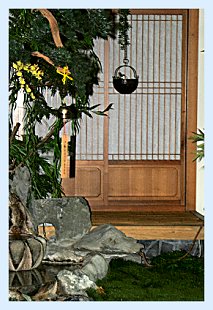

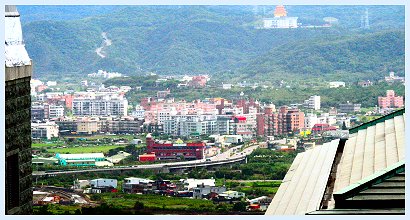

So, as I was saying, we found ourselves unexpectedly running into the Pali Canon on one of the last days of our trip through Taiwan. Specifically, we were at Dharma Drum Temple, to which is attached Dharma Drum University. As you can see by the picture, if you choose your university by its view rather than its worldview, it has a lot going for it (perhaps tempered a bit if I tell you that the big building across the valley is a crematorium).

So, as I was saying, we found ourselves unexpectedly running into the Pali Canon on one of the last days of our trip through Taiwan. Specifically, we were at Dharma Drum Temple, to which is attached Dharma Drum University. As you can see by the picture, if you choose your university by its view rather than its worldview, it has a lot going for it (perhaps tempered a bit if I tell you that the big building across the valley is a crematorium).

Before going on I might just note that this entry is somewhat long and technical; perhaps even "geeky." Please bear with me. It all leads up to some worthwhile points.

The so-called Pali Canon is a collection of writings of truly encyclopedic proportion. The name is simply based on the fact that its largest and most likely oldest surviving version is in the language called "Pali," which is possibly the language that the Buddha spoke. Pali is one of the several languages that spun off Sanskrit. The Pali Canon is also called Tipitaka, the "Three Baskets," because it has three divisions: rules for Buddhist monks, teachings of the Buddha, and scholarly analysis of Buddhist teachings.

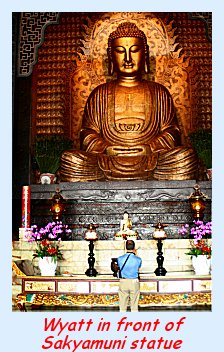

As we mentioned last time, according to tradition, much of the teaching material was recollected and dictated by Ananda, Buddha's own disciple, at the first Buddhist council in the early fifth century B.C. If a particular issue came up, or if someone was trying to recollect specifically what Sakyamuni had said, Ananda would concentrate, begin with the words "Thus have I heard," and then start to recite what was supposed to have been pretty much verbatim the words of Sakyamuni. Of course, many scholars, particularly those who are having a hard time believing that there even was a historical Buddha (Sakyamuni), question the accuracy of these alleged recollections. However, as I keep contending, we Christians need to be careful not to buy into the unfounded skepticism of religious scholarship that we so heartily reject for the Bible, when it is applied to other religious texts. Furthermore, I've known people who have had the kind of auditory memory that is being ascribed to Ananda. So, to put things cautiously, it is credible that the Pali canon does, indeed, contain some of the direct teachings of Sakyamuni.

Still, over the centuries, the Tipitaka swelled by constant addition of new material. Some of it, no doubt, consisted of the rewriting of popular traditions into Buddhist thought forms. The complete Pali canon stems from no earlier than the first century B.C. The Pali version of the Tipitaka is the most complete, and although some of it may be a fairly accurate rendering of the first generations of copies of the original as well as the first appearances of additions, there are other versions of it, some of which include different material: several in Sanskrit, and others translated into Chinese, Korean, and Tibetan. The overarching problem for scholars analyzing the early manuscripts is not textual precision--that is a lost cause---but simply identifying passages that may or may not have been a part of the original. Starting about the thirteenth century, there are wooden print blocks of it in Chinese and Korean, and so from that point on the translated texts into those languages have stabilized themselves.

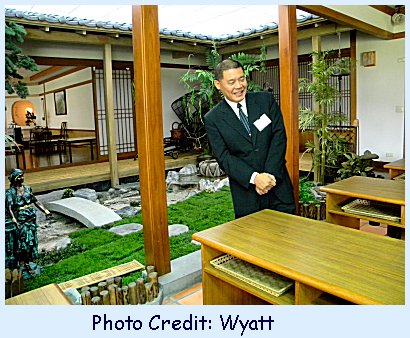

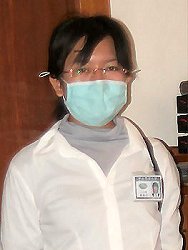

So, anyway, since the visit to Dharma Drum came towards the end of the trip, I won't get into the specifics now, except as they impinge on this discussion. I never really caught our guide's name (a volunteer, not a monk), but his name tag revealed that it was

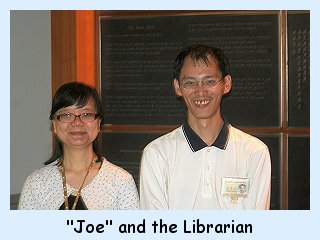

So, anyway, since the visit to Dharma Drum came towards the end of the trip, I won't get into the specifics now, except as they impinge on this discussion. I never really caught our guide's name (a volunteer, not a monk), but his name tag revealed that it was  . Let's call him "Joe" since that's a little easier on the orthography. I guess I must also mention that we distinguished ourselves a little bit by asking our friend some questions early on in the tour that he couldn't answer, and so he called in an American professor of Tibetan Buddhism at Dharma Drum University. He answered them in the common academic manner by providing nomenclature rather than insight, but we had a pleasant chat. Regardless, my point is simply that we manifested a bit more intellectual curiosity than they were used to.

. Let's call him "Joe" since that's a little easier on the orthography. I guess I must also mention that we distinguished ourselves a little bit by asking our friend some questions early on in the tour that he couldn't answer, and so he called in an American professor of Tibetan Buddhism at Dharma Drum University. He answered them in the common academic manner by providing nomenclature rather than insight, but we had a pleasant chat. Regardless, my point is simply that we manifested a bit more intellectual curiosity than they were used to.

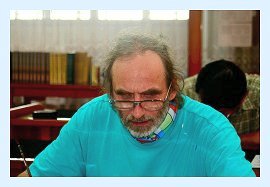

(Jimm W., skip this paragraph please.  ) Based on that impression, after lunch, Joe suggested that we visit the library, a thought that did not particularly inspire me since it was located several hundreds of steps up a hill, and libraries are not usually places you visit for just a few moments, and you have to be really quiet, and you have to be extra careful not to spill anything, and they never ever let you run, not that I wanted to. But since I did not particularly stress those matters, I was out-consensused, and we made our way up and entered the bibliophilic premises.

) Based on that impression, after lunch, Joe suggested that we visit the library, a thought that did not particularly inspire me since it was located several hundreds of steps up a hill, and libraries are not usually places you visit for just a few moments, and you have to be really quiet, and you have to be extra careful not to spill anything, and they never ever let you run, not that I wanted to. But since I did not particularly stress those matters, I was out-consensused, and we made our way up and entered the bibliophilic premises.

I changed my mind.

I changed my mind.

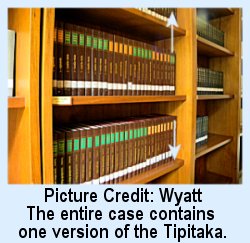

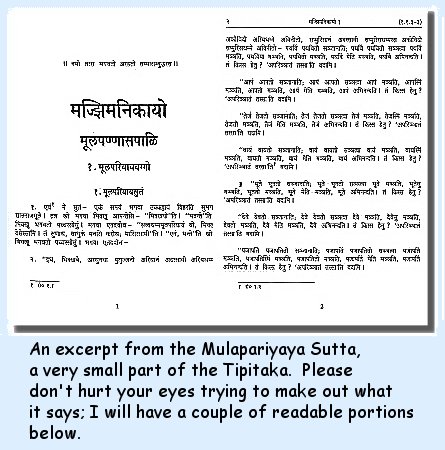

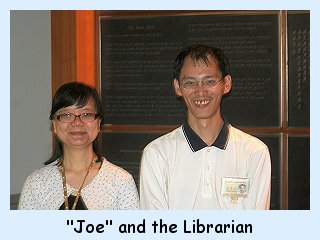

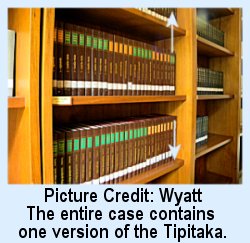

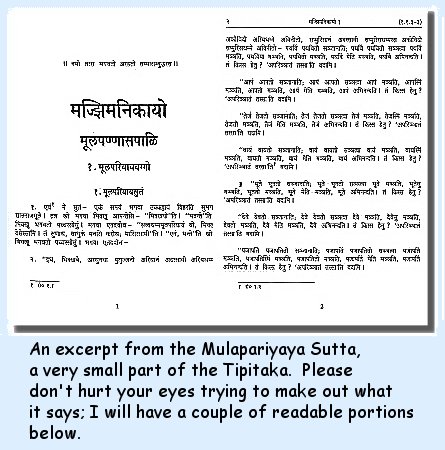

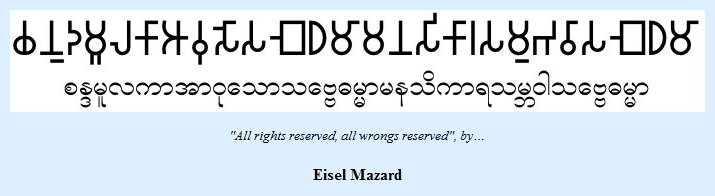

The part of the library that Joe wanted us to see was a collection of various versions of the Pali Canon: some authentic ancient ones (to which we did not have tactile access), reproductions of ancient ones, and multi-multi-volume translations into both ancient and modern languages. Wyatt had been excited all along, and now all my fatigue left me instantaneously. We could have spent hours there. Joe and a very pleasant librarian (who, by the way, never once shushed us), offered to xerox for us a page from the Pali version, and I've copied it here.

It is the beginning of the Mulapariyaya Sutta, for which you can find a complete translation and introduction by Thanissaro Bikkhu on the website Access to Insight: Introduction to Theravada Buddhism, literally the Sutra about the Conversation on the Root.

Here is where I'm asking you to hang in, even if this looks pretty off-putting at first, and you've never seen anything like this before nor would you have chosen to. As you will see, this is a lot like a game, actually. If you've had any experience with Hindi or Sanskrit, you will immediately recognize that Pali uses the Devanagari alphabet. The most obvious difference that strikes the eye is the dissimilarity in the spelling of various words. Not that there aren't also grammatical differences to Sanskrit, but it's the spelling that really stands out.

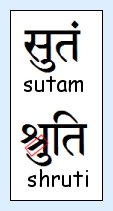

Okay, novices and budding experts togther, let's start with the word sutta. It is, of course, the Pali variation of the word sutra. So, in the title

(mulapariyayamsuttam),

the last part reads  (sutta) rather than

(sutta) rather than  (sutra) as it would in Sanskrit. The little dot over the final character in the Pali means that the "a" is nasalyzed. By the way, the thing that looks like a question mark is the numeral "1," and the period after it is a concession to Western conventions. It is, after all, a contemporary printing.

(sutra) as it would in Sanskrit. The little dot over the final character in the Pali means that the "a" is nasalyzed. By the way, the thing that looks like a question mark is the numeral "1," and the period after it is a concession to Western conventions. It is, after all, a contemporary printing.

So, what did we notice with the word "sutra" as it was transformed into Pali? Pali became more nasal in its pronunciation, but--much more importantly, it dropped the "r" and doubled the consonant. This is a pattern we encounter throughout. Here is an example from the top of the second page:

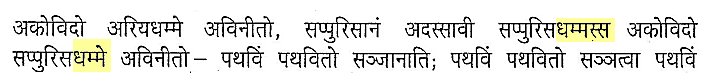

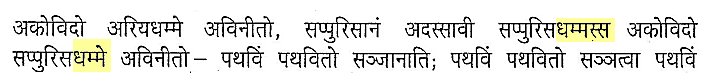

I highlighted two uses of the word  (dhamma), which is the Pali version of the word

(dhamma), which is the Pali version of the word  (dharma), whose meaning includes everything from the fundamental rules of the universe to the truth of Buddhism to the means towards enlightenment. If you read the Venerable Thanissaro's translation of this sutra, you'll see that in this case it refers to the rules of the nobility (lit. the Aryans) and the righteous men (lit. the "sannyasin," i.e. monks who have withdrawn from the world), of whose dharma the hypothetical common person is ignorant. But to come back to the language, the Devanagari alphabet has many ways of indicating the letter "r," which is considered a semi-vowel. In dharma it is indicated by that half loop over the last character, which is a "ma." So dharma in Sanskrit becomes dhamma in Pali. Sometimes the consonant changes slightly as well. Thus, for example, nirvana (Sanskrit) becomes nibbana (Pali).

(dharma), whose meaning includes everything from the fundamental rules of the universe to the truth of Buddhism to the means towards enlightenment. If you read the Venerable Thanissaro's translation of this sutra, you'll see that in this case it refers to the rules of the nobility (lit. the Aryans) and the righteous men (lit. the "sannyasin," i.e. monks who have withdrawn from the world), of whose dharma the hypothetical common person is ignorant. But to come back to the language, the Devanagari alphabet has many ways of indicating the letter "r," which is considered a semi-vowel. In dharma it is indicated by that half loop over the last character, which is a "ma." So dharma in Sanskrit becomes dhamma in Pali. Sometimes the consonant changes slightly as well. Thus, for example, nirvana (Sanskrit) becomes nibbana (Pali).

So, with a little bit of luck you can take a Pali word and make an educated guess as to what its Sanskrit predecessor might have been. I called the "Three Baskets" the Tipitaka. That is the Pali word for it. What might it be in Sanskrit? You're right: It's Tripitaka. Since there were no doubled consonants, the original "r" must have been at the front of the word, and so we just needed to add it there. The syllable tri also shows us how nicely Sanskrit lines up with general Indo-European patterns. We didn't get the use of "tri" to indicate "three-ness" from Sanskrit, nor did they get it from us nor the Romans nor the Greeks; it's a part of our common I-E heritage.

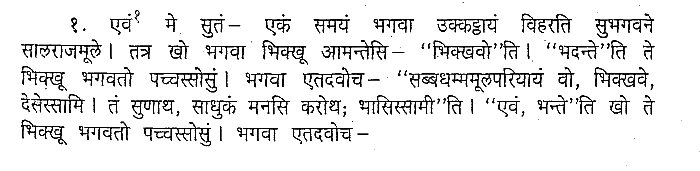

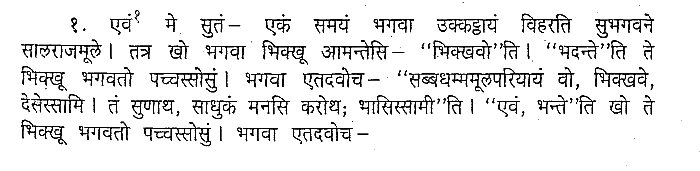

Let's now take a quick look at the first paragraph.

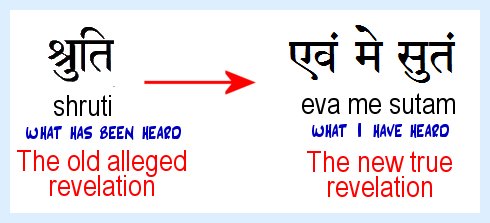

The quotation marks, commas, and dashes, not to mention the footnote indicator, are additional accommodations to Western style. Classical punctuation consisted of only two signs:  the first one designating a short break, such as after a line in a poem, the second one calling for a full stop (thus resembling a comma and a period respectively). The first words constitute the famous formula ascribed to Ananda and copied by imitators and forgers ever since:

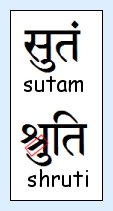

the first one designating a short break, such as after a line in a poem, the second one calling for a full stop (thus resembling a comma and a period respectively). The first words constitute the famous formula ascribed to Ananda and copied by imitators and forgers ever since:  Eva me sutam. ("Thus have I heard.") It occurs to me that there could be some confusion between suta here and sutta earlier.

Eva me sutam. ("Thus have I heard.") It occurs to me that there could be some confusion between suta here and sutta earlier.  sutta ("sutra")and

sutta ("sutra")and  suta ("heard") are two different words. See if you can find the little line that doubles the letter "t." in sutta !

suta ("heard") are two different words. See if you can find the little line that doubles the letter "t." in sutta !

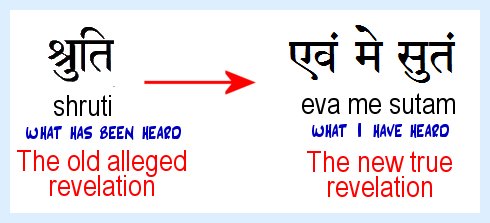

Ok, then, if you try to revert suta back to Sanskrit and follow the previous formula, how would you do so? You have only one consonant in the middle, and if you just add an "r," you would get the same word sutra again. But that wouldn't make sense for Sanskrit any more than we just said it would for Pali. So, just like with tipitaka/tripitaka, we have to look at the front of the word again. But in this case it's just a little more complicated. To turn the Pali back into Sanskrit, you also have to change the type of "s" from the straight-forward hissing sound to one that's better transliterated as "sh," and then you do add the "r" to it, resulting "shr." I drew a little red rectangle around the little bar that stands for the "r" in this instance. Now make one further grammatical adjustment and you get shruti, the word that is used in Hinduism to refer to the holiest texts, such as the Vedas, those that were supposed to have been "heard" by the rishis ("holy semi-divine seers") of ancient days.

Ok, then, if you try to revert suta back to Sanskrit and follow the previous formula, how would you do so? You have only one consonant in the middle, and if you just add an "r," you would get the same word sutra again. But that wouldn't make sense for Sanskrit any more than we just said it would for Pali. So, just like with tipitaka/tripitaka, we have to look at the front of the word again. But in this case it's just a little more complicated. To turn the Pali back into Sanskrit, you also have to change the type of "s" from the straight-forward hissing sound to one that's better transliterated as "sh," and then you do add the "r" to it, resulting "shr." I drew a little red rectangle around the little bar that stands for the "r" in this instance. Now make one further grammatical adjustment and you get shruti, the word that is used in Hinduism to refer to the holiest texts, such as the Vedas, those that were supposed to have been "heard" by the rishis ("holy semi-divine seers") of ancient days.

Now we get to the pay-off. What does the little formula, "Eva me sutam--Thus have I heard" really indicate then? It's a reappropriation of the notion of shruti, indicating that the text that is about to follow is the real shruti. Buddhism is sometimes considered to be one of the two "heretical" schools of Hinduism (the other one being Jainism), primarily for two reasons. It rejected the caste system, which was already finding its place in Indian society in the sixth century B.C., and it rejected the authority of the Vedas and their accompanying texts, all of which are considered shruti. So, instead of the Hindu shruti, we get the new shruti, except that it is now expressed in Pali with the phrase: eva me sutam. In other words, the new formula may be a compliment to Ananda's memorization skills, but that's neither here nor there. More significantly, it is a dramatic claim: "You are about to hear the genuine revealed truth."

This is, of course, only a relatively minor insight, which presents little surprise in the history of religions. And I could have simply told you this right at the beginning without confusing you with all those illegible symbols. ---- But wait! What makes them illegible? They are, after all, languages, encoded in an alphabet. If they are illegible to you, it's because you don't know the languages, and I don't blame you if you don't. Most likely, you've never even had much of an opportunity to learn them. I've had to teach myself.

Thus, we come to my polemic. Serious evangelical Christian seminaries have their students become competent in all three biblical languages: Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, and we justifiedly react negatively to those who interpret the Bible in direct contradiction to what it plainly says in its original languages or to those, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, who clearly distort the Greek text in order to support their heretical doctrines. Furthermore, some of the best schools offer the opportunity to delve deeper into the ancient languages prior to and coterminous with the Old Testament: Moabite, Akkadian, Edomite, Egyptian, etc. This is very good because it contributes to our understanding of the biblical text and biblical history. I would not want one less credit unit of these ancient languages offered or taken.

However, here is another point to consider. For quite a while now, neither Moabites nor Akkadians have provided too many significant intellectual challenges to the truth of Christianity. Whatever is written by them is past history. On the other hand, Buddhism is alive and well and intent on swallowing up Christianity, and if we want to do any meaningful apologetics, we have to be able to read their scriptures in their languages. How do I know whether Ven. Thanissaro's very elegant translation of the Root Sutra is accurate or whether he is deliberately covering up items that could possibly turn off the people he might be trying to reach? How can we know whether the Theravada Buddhism presented on that site really is Theravada Buddhism or just an accommodation to Western tastes? (For what it's worth, from my vantage point, this appears to me to be an excellent site and a good translation.) Without knowing some Pali, we won't be able to make such assessments. Many of the more popular translations of Eastern scriptures into English bear only a faint resemblance to what they say in their originals. For example, a popular translation of the Bhagavad Gita makes references to churches and mosques. Are they really there in the Sanskrit text? How will you respond to someone who brings up that passage (without writing an e-mail to me  )?

)?

And I'm wondering--and this is a radical thought--are any Christian schools at all contemplating training their students in classical Eastern languages?

This has been a long entry, written sporadically over a strenuous weekend trip visiting June's aging and ailing Mom in Michigan. I thank you for reading this, and I hope that you might catch both my excitement for this kind of study and the ache in my heart for those who need the truth. I'm praying that Christians who are excited about apologetics would also become excited about the hard study necessary to do apologetics well. We cannot afford another generation of American Christians who spread the absurd notion that Buddhism is a form of pantheism. Buddhism has come too close to us to keep getting it wrong. (Hint: Look at the courses offered at major universities these days.)

Next time a culinary topic: Lunch with the monks and nuns at the monastery.

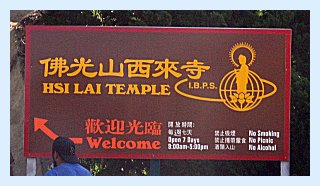

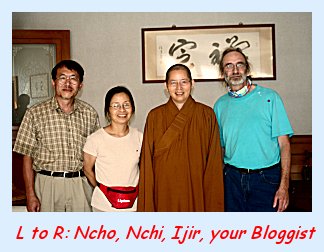

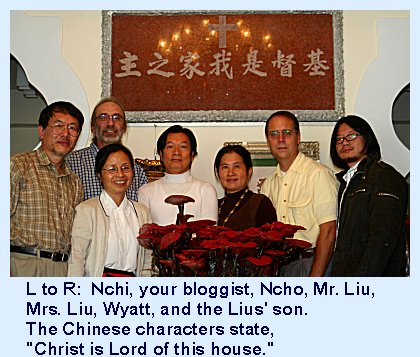

Those who have hung around my blog for a while know that I tend not to advertise overseas trips indiscriminately in advance. Sorry if you're disappointed, let alone upset, if you got left out of the loop, which has a rather short diameter, but there are several strong reasons for it. For those of you who knew, thanks for your thoughts and prayer support. The objective of the trip was to visit a plethora of Buddhist temples in Taiwan and to talk to converts from Buddhism to Christianity. The team consisted of Wyatt, who is my friend and has been my companion on several previous trips abroad, Ntchotchi (hereafter: "Ncho") along with her husband Intchutchuna (hereafter: "Nchi"). Oh yeah, you might not find them listed under those names in the phone book either. I'm not meaning to be overdramatic (if I were, I would have to disguise my identity also and not publish any pictures), but just following some basic measures for publishing something unrestricted on the web. In Taiwan, we were joined on most days by Wa-ta-wa (hereafter "Wa"), a Buddhist college professor, who opened many a door for us.

Those who have hung around my blog for a while know that I tend not to advertise overseas trips indiscriminately in advance. Sorry if you're disappointed, let alone upset, if you got left out of the loop, which has a rather short diameter, but there are several strong reasons for it. For those of you who knew, thanks for your thoughts and prayer support. The objective of the trip was to visit a plethora of Buddhist temples in Taiwan and to talk to converts from Buddhism to Christianity. The team consisted of Wyatt, who is my friend and has been my companion on several previous trips abroad, Ntchotchi (hereafter: "Ncho") along with her husband Intchutchuna (hereafter: "Nchi"). Oh yeah, you might not find them listed under those names in the phone book either. I'm not meaning to be overdramatic (if I were, I would have to disguise my identity also and not publish any pictures), but just following some basic measures for publishing something unrestricted on the web. In Taiwan, we were joined on most days by Wa-ta-wa (hereafter "Wa"), a Buddhist college professor, who opened many a door for us.

Third, if you're waiting for stories on what we did for fun, you apparently never took my regular world religions class (before my energy started to give out), and so you aren't aware of the fact there is nothing more fun for me than visiting temples (. . . well, and playing music and watching auto races and doing web sites . . . ). Anyway, we spent an enormous amount of time just traveling back and forth, and I used a lot of that time for zombying out. We did not go surfing or rock climbing.

Third, if you're waiting for stories on what we did for fun, you apparently never took my regular world religions class (before my energy started to give out), and so you aren't aware of the fact there is nothing more fun for me than visiting temples (. . . well, and playing music and watching auto races and doing web sites . . . ). Anyway, we spent an enormous amount of time just traveling back and forth, and I used a lot of that time for zombying out. We did not go surfing or rock climbing.

So, as I was saying, we found ourselves unexpectedly running into the Pali Canon on one of the last days of our trip through Taiwan. Specifically, we were at Dharma Drum Temple, to which is attached Dharma Drum University. As you can see by the picture, if you choose your university by its view rather than its worldview, it has a lot going for it (perhaps tempered a bit if I tell you that the big building across the valley is a crematorium).

So, as I was saying, we found ourselves unexpectedly running into the Pali Canon on one of the last days of our trip through Taiwan. Specifically, we were at Dharma Drum Temple, to which is attached Dharma Drum University. As you can see by the picture, if you choose your university by its view rather than its worldview, it has a lot going for it (perhaps tempered a bit if I tell you that the big building across the valley is a crematorium).  So, anyway, since the visit to Dharma Drum came towards the end of the trip, I won't get into the specifics now, except as they impinge on this discussion. I never really caught our guide's name (a volunteer, not a monk), but his name tag revealed that it was

So, anyway, since the visit to Dharma Drum came towards the end of the trip, I won't get into the specifics now, except as they impinge on this discussion. I never really caught our guide's name (a volunteer, not a monk), but his name tag revealed that it was  ) Based on that impression, after lunch, Joe suggested that we visit the library, a thought that did not particularly inspire me since it was located several hundreds of steps up a hill, and libraries are not usually places you visit for just a few moments, and you have to be really quiet, and you have to be extra careful not to spill anything, and they never ever let you run, not that I wanted to. But since I did not particularly stress those matters, I was out-consensused, and we made our way up and entered the bibliophilic premises.

) Based on that impression, after lunch, Joe suggested that we visit the library, a thought that did not particularly inspire me since it was located several hundreds of steps up a hill, and libraries are not usually places you visit for just a few moments, and you have to be really quiet, and you have to be extra careful not to spill anything, and they never ever let you run, not that I wanted to. But since I did not particularly stress those matters, I was out-consensused, and we made our way up and entered the bibliophilic premises. I changed my mind.

I changed my mind.

the first one designating a short break, such as after a line in a poem, the second one calling for a full stop (thus resembling a comma and a period respectively). The first words constitute the famous formula ascribed to Ananda and copied by imitators and forgers ever since:

the first one designating a short break, such as after a line in a poem, the second one calling for a full stop (thus resembling a comma and a period respectively). The first words constitute the famous formula ascribed to Ananda and copied by imitators and forgers ever since:  Ok, then, if you try to revert suta back to Sanskrit and follow the previous formula, how would you do so? You have only one consonant in the middle, and if you just add an "r," you would get the same word sutra again. But that wouldn't make sense for Sanskrit any more than we just said it would for Pali. So, just like with tipitaka/tripitaka, we have to look at the front of the word again. But in this case it's just a little more complicated. To turn the Pali back into Sanskrit, you also have to change the type of "s" from the straight-forward hissing sound to one that's better transliterated as "sh," and then you do add the "r" to it, resulting "shr." I drew a little red rectangle around the little bar that stands for the "r" in this instance. Now make one further grammatical adjustment and you get shruti, the word that is used in Hinduism to refer to the holiest texts, such as the Vedas, those that were supposed to have been "heard" by the rishis ("holy semi-divine seers") of ancient days.

Ok, then, if you try to revert suta back to Sanskrit and follow the previous formula, how would you do so? You have only one consonant in the middle, and if you just add an "r," you would get the same word sutra again. But that wouldn't make sense for Sanskrit any more than we just said it would for Pali. So, just like with tipitaka/tripitaka, we have to look at the front of the word again. But in this case it's just a little more complicated. To turn the Pali back into Sanskrit, you also have to change the type of "s" from the straight-forward hissing sound to one that's better transliterated as "sh," and then you do add the "r" to it, resulting "shr." I drew a little red rectangle around the little bar that stands for the "r" in this instance. Now make one further grammatical adjustment and you get shruti, the word that is used in Hinduism to refer to the holiest texts, such as the Vedas, those that were supposed to have been "heard" by the rishis ("holy semi-divine seers") of ancient days.

)?

)?

Now, the key for my decisions on what to try was the rule that if you start an item, you must finish it (though I had already decided that if something would turn out to be utterly impossible to get down, I would bank on the forgiveness that had been promised earlier).

Now, the key for my decisions on what to try was the rule that if you start an item, you must finish it (though I had already decided that if something would turn out to be utterly impossible to get down, I would bank on the forgiveness that had been promised earlier).

There is no telling what was going on in her mind as she next turned to Wyatt and asked him about his story. Wyatt knew potential overkill when it was lurking, and gave a more abridged version of his conversion, but also highlighted that he did not become a Christian until he was in college. After a little more conversation, we moved on to the big Buddha Hall.

There is no telling what was going on in her mind as she next turned to Wyatt and asked him about his story. Wyatt knew potential overkill when it was lurking, and gave a more abridged version of his conversion, but also highlighted that he did not become a Christian until he was in college. After a little more conversation, we moved on to the big Buddha Hall.

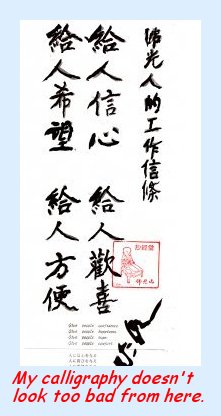

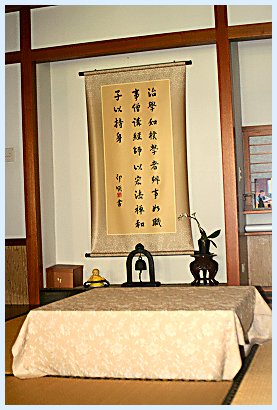

After we had produced our master (Nchi), journeyman (Wyatt), and pre-apprentice (your bloggist) pieces, the teacher dried them, gave them an official stamp, and wrapped them up as little scrolls. In case you're wondering, the text we were copying says,

After we had produced our master (Nchi), journeyman (Wyatt), and pre-apprentice (your bloggist) pieces, the teacher dried them, gave them an official stamp, and wrapped them up as little scrolls. In case you're wondering, the text we were copying says, Our last stop at the temple grounds was the gift shop, which, similar to most gift shops around the world, contained a lot of stuff made in Taiwan, though they passed it off as home-made here. (Sometimes I truly crack myself up.) The shop was actually a little sheltered outdoor nook with some soothing Chinese music in the background. Ncho sought for and purchased one of those wide Chinese straw hats. As soon as we entered the premises, Ijir gave some directions to one of the workers there, who immediately changed the music to a rather catchy tune sung by a group in English. The lyrics were of the standard "let's-change-the-world-with-the-dharma-of-unity" variety. Actually, I remember more of the words a little more accurately. Furthermore, both Wyatt and I, though neither one of us is terribly knowledgeable when it comes to contemporary Christian music, were pretty convinced it was originally a Christian song of relatively recent vintage, apparently adopted and adapted by the Chinese temple to provide a more attractive ambience for Western visitors. I am simply relating our impressions, and I won't give any more details because there is a difference between being personally fairly certain of something and being able to swear to it in court. For all that I know, although it seems unlikely to me, the Buddhists may have bought the rights to the song. My main point is that the Buddhists are learning the skill of contextualization.

Our last stop at the temple grounds was the gift shop, which, similar to most gift shops around the world, contained a lot of stuff made in Taiwan, though they passed it off as home-made here. (Sometimes I truly crack myself up.) The shop was actually a little sheltered outdoor nook with some soothing Chinese music in the background. Ncho sought for and purchased one of those wide Chinese straw hats. As soon as we entered the premises, Ijir gave some directions to one of the workers there, who immediately changed the music to a rather catchy tune sung by a group in English. The lyrics were of the standard "let's-change-the-world-with-the-dharma-of-unity" variety. Actually, I remember more of the words a little more accurately. Furthermore, both Wyatt and I, though neither one of us is terribly knowledgeable when it comes to contemporary Christian music, were pretty convinced it was originally a Christian song of relatively recent vintage, apparently adopted and adapted by the Chinese temple to provide a more attractive ambience for Western visitors. I am simply relating our impressions, and I won't give any more details because there is a difference between being personally fairly certain of something and being able to swear to it in court. For all that I know, although it seems unlikely to me, the Buddhists may have bought the rights to the song. My main point is that the Buddhists are learning the skill of contextualization.

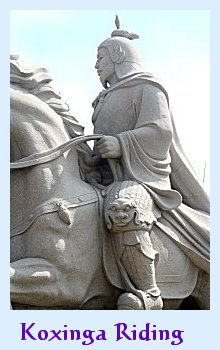

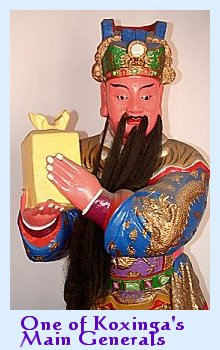

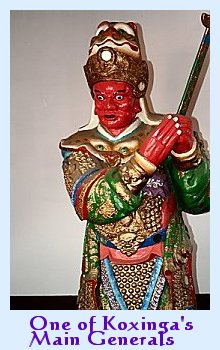

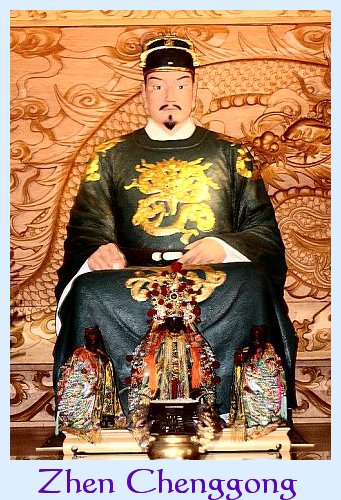

Well, that's all we need to include of this interlude entry. Next time we'll get back to Taiwan. What do you say, let'stalk about pirates and not just one, but several emperors and the pirate's son who becomes a god? And it won't be one of those kissing stories either.

Well, that's all we need to include of this interlude entry. Next time we'll get back to Taiwan. What do you say, let'stalk about pirates and not just one, but several emperors and the pirate's son who becomes a god? And it won't be one of those kissing stories either.

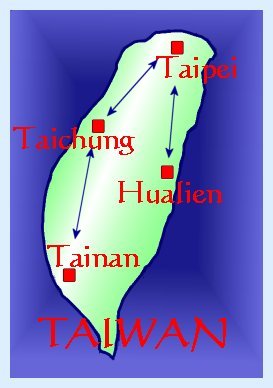

So, Monday turned into a travel day, and I suspect I probably got more rest sitting in the trains than I would have staying in Tainan. The arrows on the map indicate our route to Hualien. Even though it's a lengthy track and backtrack, it's still the quicker way to go than to try to cut across.

So, Monday turned into a travel day, and I suspect I probably got more rest sitting in the trains than I would have staying in Tainan. The arrows on the map indicate our route to Hualien. Even though it's a lengthy track and backtrack, it's still the quicker way to go than to try to cut across.

The Integration of Faith and Learning.

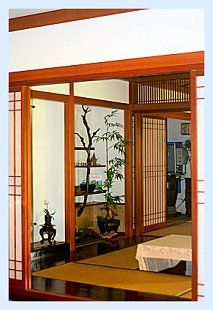

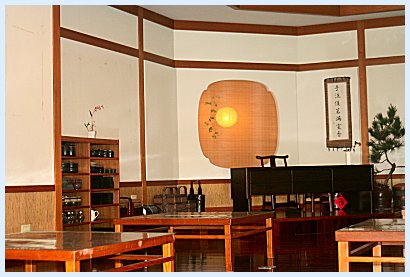

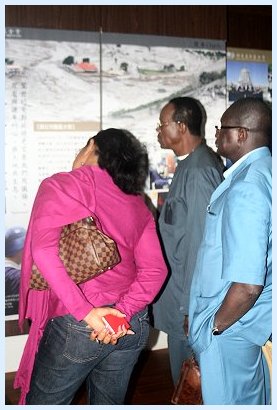

The Integration of Faith and Learning.  In this case, however, we're talking about the the integration of Buddhist faith and learning, and a university that appears committed to do so thoroughly, Tzu Chi University of Hualien, Taiwan. Before closing out our all-too-short visit to colorful Hualien, early Wednesday morning we visited the Tzu Chi center, which includes a university, an administrative center with temple/sanctuay, and a hospital. We skipped the hospital and started out with the university because our tour of the main center was going to be coordinated with a visit by some senators from the country of Nigeria. The gentleman who coordinated the visit for us had to do some serious multitasking trying to keep on schedule, so he turned us over to the public relations official of the university.

In this case, however, we're talking about the the integration of Buddhist faith and learning, and a university that appears committed to do so thoroughly, Tzu Chi University of Hualien, Taiwan. Before closing out our all-too-short visit to colorful Hualien, early Wednesday morning we visited the Tzu Chi center, which includes a university, an administrative center with temple/sanctuay, and a hospital. We skipped the hospital and started out with the university because our tour of the main center was going to be coordinated with a visit by some senators from the country of Nigeria. The gentleman who coordinated the visit for us had to do some serious multitasking trying to keep on schedule, so he turned us over to the public relations official of the university.  The representative of TCU could not have fit better into his role if he had been selected by a Hollywood casting agency. He combined just the right amounts of enthusiasm for the school, devotion to its Buddhist commitment, sincerity towards us as visitors (who, for all that he knew, might at any moment open our checkbooks for a sizable donation), and the dignified bearing of a professional and experienced undertaker. Even though the last attribute may sound just a bit overstereotyped, it turned out that it was, indeed, highly appropriate for his function.

The representative of TCU could not have fit better into his role if he had been selected by a Hollywood casting agency. He combined just the right amounts of enthusiasm for the school, devotion to its Buddhist commitment, sincerity towards us as visitors (who, for all that he knew, might at any moment open our checkbooks for a sizable donation), and the dignified bearing of a professional and experienced undertaker. Even though the last attribute may sound just a bit overstereotyped, it turned out that it was, indeed, highly appropriate for his function.

As I mentioned, the video became somewhat wearisome, but the promotion of this exciting opportunity did not stop there. You would think that there would be much more to see in this school than their body-acquisition program, but next we paid a visit to the anatomical lab, where we saw not much more than the storage facilities. Having worked as orderly in hospitals a long time ago, when a part of my job was to take the deceased into the morgue and store them in the refrigerated compartments, there was nothing new here for me. (BTW, remind me to tell you all about that duty some day.)

As I mentioned, the video became somewhat wearisome, but the promotion of this exciting opportunity did not stop there. You would think that there would be much more to see in this school than their body-acquisition program, but next we paid a visit to the anatomical lab, where we saw not much more than the storage facilities. Having worked as orderly in hospitals a long time ago, when a part of my job was to take the deceased into the morgue and store them in the refrigerated compartments, there was nothing new here for me. (BTW, remind me to tell you all about that duty some day.) Once we were back at the main center, our original guide took over again. We had no sooner entered the premises, than we were greeted by a group of five women who had attained the highest status as members of the Tzu Chi society. In an effort to contextualize their welcome to us Christians (and perhaps because one or more of them had seen Once Upon a Time in China, part 1, starring Jet Li--highly recommended by your bloggist), their greeting consisted of their chanting "Hallelujah" multiple times. A word of caution to anyone: you don't necessarily build a bridge to another culture or religion by repeating phrases out of their argot in a meaningless way. As we learned subsequently, these women had attained the highest ranks in the society, which is based on participation in so many world-wide acts of rescue, which can take the form of contributing a great amount of money as the society carries out its mission.

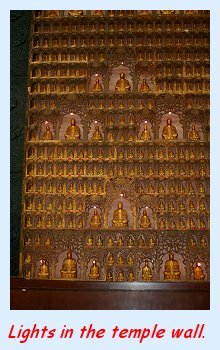

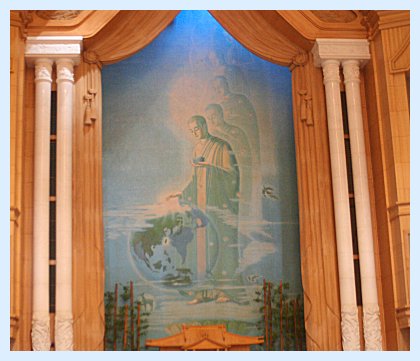

Once we were back at the main center, our original guide took over again. We had no sooner entered the premises, than we were greeted by a group of five women who had attained the highest status as members of the Tzu Chi society. In an effort to contextualize their welcome to us Christians (and perhaps because one or more of them had seen Once Upon a Time in China, part 1, starring Jet Li--highly recommended by your bloggist), their greeting consisted of their chanting "Hallelujah" multiple times. A word of caution to anyone: you don't necessarily build a bridge to another culture or religion by repeating phrases out of their argot in a meaningless way. As we learned subsequently, these women had attained the highest ranks in the society, which is based on participation in so many world-wide acts of rescue, which can take the form of contributing a great amount of money as the society carries out its mission.  After a time, we were joined by the expected team of senators from Nigeria. As Wyatt pointed out to me, the dynamics changed immediately, as these men and women were obviously accorded higher standing than us and took precedence (actually I did not get the feeling from them that they saw it that way; after all, they got to meet the great Wyatt in person, but that's what the dynamics were). They sat in front of us for another lengthy video, and they received a greater amount of attention than we did. We didn't get snubbed, and the atmosphere suited us fine. It was just interesting to see the layers of respect emerge when we toured the building. It had a lot of glass-encased representations of the Tzu Chi society at work. We rested in a pretty sizeable sanctuary with padded seats, which was dominated by a picture of a Buddha or Bodhisattva figure who was caring for the world, the idea being that the society, thanks to the Buddha, would create a "pure land" on earth. Our guide took questions, and all of them, as I recall, came from the Nigerian delegation. In contrast to our group, they were not particularly acquainted with Buddhism, and a lot of what they asked about had to do with the basic tenets of Buddhism and particularly with reincarnation.

After a time, we were joined by the expected team of senators from Nigeria. As Wyatt pointed out to me, the dynamics changed immediately, as these men and women were obviously accorded higher standing than us and took precedence (actually I did not get the feeling from them that they saw it that way; after all, they got to meet the great Wyatt in person, but that's what the dynamics were). They sat in front of us for another lengthy video, and they received a greater amount of attention than we did. We didn't get snubbed, and the atmosphere suited us fine. It was just interesting to see the layers of respect emerge when we toured the building. It had a lot of glass-encased representations of the Tzu Chi society at work. We rested in a pretty sizeable sanctuary with padded seats, which was dominated by a picture of a Buddha or Bodhisattva figure who was caring for the world, the idea being that the society, thanks to the Buddha, would create a "pure land" on earth. Our guide took questions, and all of them, as I recall, came from the Nigerian delegation. In contrast to our group, they were not particularly acquainted with Buddhism, and a lot of what they asked about had to do with the basic tenets of Buddhism and particularly with reincarnation.  Now, I need to pause here for a moment for some careful reflection. For many years now, I have maintained that, even though the world loves to blame Christianity for many alleged evils, not many groups other than Christians go out and serve others sacrificially, especially when they are not of their faith and the chances of conversion are slim. Where are the Soka Gakkai hospitals for lepers or the Islamic fund raising activities for non-Muslim victims of the Tsunami a little while ago? There are a few groups, such as the Ramakrishna Society, that have attempted to imitate Christian missions of mercy with limited success, but on the whole, non-Christian religions are as likely to interfere with Christian missions of mercy as they are unlikely to undertake their own initiatives.

Now, I need to pause here for a moment for some careful reflection. For many years now, I have maintained that, even though the world loves to blame Christianity for many alleged evils, not many groups other than Christians go out and serve others sacrificially, especially when they are not of their faith and the chances of conversion are slim. Where are the Soka Gakkai hospitals for lepers or the Islamic fund raising activities for non-Muslim victims of the Tsunami a little while ago? There are a few groups, such as the Ramakrishna Society, that have attempted to imitate Christian missions of mercy with limited success, but on the whole, non-Christian religions are as likely to interfere with Christian missions of mercy as they are unlikely to undertake their own initiatives.

No, it never wears off. I am always excited when something I have written appears in print. And I still get totally goosebumped whenever someone whom I've never met sends me an e-mail and tells me that the Lord used whatever I may have written in his or her life. So, I'm pleased that I've received my copies of the May/June issue of Areopagus Journal (I think they're somewhat behind), and that it contains my article, "Hinduism: Empty Diversity," followed by Keith Yandell (University of Wisconsin) on Buddhism and by Pat Zukeran (Probe Ministries) on Confucianism and Daoism. The issue also contains a good exposition on the sometimes famous, but almost always misrepresented, Falun Gong by Clete Hux of the

No, it never wears off. I am always excited when something I have written appears in print. And I still get totally goosebumped whenever someone whom I've never met sends me an e-mail and tells me that the Lord used whatever I may have written in his or her life. So, I'm pleased that I've received my copies of the May/June issue of Areopagus Journal (I think they're somewhat behind), and that it contains my article, "Hinduism: Empty Diversity," followed by Keith Yandell (University of Wisconsin) on Buddhism and by Pat Zukeran (Probe Ministries) on Confucianism and Daoism. The issue also contains a good exposition on the sometimes famous, but almost always misrepresented, Falun Gong by Clete Hux of the