by which he would like us to live. There are three fundamental principles:

by which he would like us to live. There are three fundamental principles:

This website is a collection of entries from my blog appearing sporadically in May and June of 2009.

A little while ago someone asked me if I had any thoughts on Paul Tillich. Unfortunately, the question came via facebook on my mobile phone while we were on our way up to Chicago for ISCA. June intimated that I could just write back "yes" (though "no" might have been the more accurate answer at just about that time), but we both agreed that the question, not to mention the person asking it, deserved a better response. So, as I'm contemplating moving from "Sampling Samuel" to "Being Keen on Kings"--ouch, that's awful; I think I need some help again--let me interject "Tilling with Tillich."

Tillich was a twentieth-century theologian. Rather than classifying him off-hand as liberal, neo-orthodox, dialectical, ontological, or whatever, let me just say that he was not conservative, let alone evangelical. We'll get into more specifics in a moment. The Wikipedia article on him mentions him as one of the four leading theologians of the twentieth century, along with Karl Barth, Rudolf Bultmann, and Reinhold Niehbur. That's a pretty subjective judgment, which we can let stand by allowing that for those people who liked his kind of theology, he was among those whom they liked, along with the two B's and the big N. Personally, it occurs to me that this list stops rather early in the twentieth century and leaves out important people like Moltmann, Pannenberg, Cone, or Segundo, while including Niebuhr whose influence was more pastoral and political than theological.

I'm totally intrigued by Tillich. In one sense, of the four theologians mentioned, at first glance, he's the most far out. Barth, for example, consistently uses biblical language. He is considered to be "neo-orthodox," where the "orthodox" part refers to his use of such traditional and biblical terms as sin, atonement, salvation, justification, etc., whereas Tillich's argot consists of words such as New Being, ultimate concern, ambiguity, estrangement from your own being, and so forth. However, the "neo" part for Barth comes into play insofar as Barth accepts the conclusions of negative biblical criticism and, when you come right down to it, his theology is a Hegelian-like idealism in which God reconciles himself to himself. Faith means accepting the cosmic story as God has worked it out already. For Tillich, on the other hand, there is an "evangelistic" side that requires us to come to a personal renewal of our being in Christ.

But first we have to work through the jargon. Tillich seeks to elaborate his theology by using the words generated by a supposedly new ontology that actually looks in many ways like that of Plotinus and FJW Schelling. Here's a quick "transformational dictionary."

You get the picture.

Still, there's something about Tillich's thought that resonates with me, perhaps not as theology so much as a philosophy of life. His theological method is called the "method of correlation." This means that his theology begins with the questions of philosophy that philosophy can't answer, such as the meaning and purpose of life (iow, those that generally have "42" as an answer). Tillich says that theology picks up those questions and asks them afresh, and then theology answers them from a biblical perspective.

Did I just say biblical perspective? Is "ultimate concern in the Ground of all Being" a biblical concept? Well, yes, says Tillich, but it is the biblical concept expressed in what he considers to be contemporary terms. Therefore, if we grant Tillich all of that, we're almost looking at an evangelical theology expressed in non-evangelical terms. This is the part about Tillich that has me fascinated.

But we'll never know. The problem with the above tranformational dictionary is that it works only one way, and it's not possible to translate back. Faith, once used in a more strictly biblical sense, has become "ultimate concern." But I cannot reverse this process and turn "ultimate concern" back into biblical faith. The same thing would apply to, say, "New Being." It's supposed to be a new way of expressing the Christ-event, but I can't simply retranslate it into the person and work of Jesus Christ as understood in traditional orthodox theology.

In fact, when it comes to Christ, Tillich has placed himself into a genuine theological pickle. On the one hand, he insists that proper theology must maintain both, the Christ of faith, viz. the God-man who is the object of our ultimate concern, and Jesus of Nazareth, the man who personally revealed God. However, Jesus of Nazareth is not a person discoverable by historical methodology; his identity and life are shrouded in myth and legend.

Consequently, Tillich leaves us with words and concepts, but nothing concrete that is really helpful. What does it mean for me to be estranged from my being? I understand what that means psychologically: the feeling of self-alienation that can be a part of certain conditions or the result of some medications. But I'm clueless as to what that means theologically. Even worse, if Jesus Christ does not really refer to the identifiable Jesus of Nazareth in history, I sure don't understand what it means for me to find "New Being" in him.

In his theology Tillich confronts each one of us with our need, first to find new being in Christ, and then to rid our being increasingly of the ambiguity that besets it. We can and must respond to that call. And perhaps we would, if we knew what it meant.

I need to add one other comment on Tillich, the man, as well as the theologian. I really don't like doing that, but chances are good that if you have known anything about Tillich previously, you may be aware of the issues of his own life. On the one hand, I must admire him for standing up to Hitler, a stance that forced him to undergo quite a bit of hardship. The move to America was not easy on him. On the other hand, his personal life, with his various wives and mistresses was quite chaotic, and I'm going to suggest that perhaps Paul Tillich found his own theology as impenetrable or too abstract to be relevant as the rest of us do. You know that I don't mince words when it comes to so-called evangelical theologians either. Now, don't get all legalistic and try to measure any given person's theology by their sinlessness. Christian theology includes the notion of fallenness, and we cannot see into a person's heart. However, in drastic cases, when a person's theology seems not toimpact their personal lives on a routine basis, it's time to ask how relevant it really is--to him, to us, to the world.

Apparently some folks appreciated my thoughts on Tillich last night, so let me go on with what happened in non-evangelical theology in his wake. Tillich was a good writer and received a lot of acclaim, both in Germany and in the United States. However, the acclaim went in different directions, as I shall express in the following overstatements or caricatures. In Germany he was hailed as a deep thinker who authored an ingenious synthesis of philosophy and theology, a teutonic Aquinas, who was making theology adaptable to modern culture--but who did not make any real progress, an important value in a country where theology is still an important department in state universities.

In America, however, Tillich's theology became the starter's gun for a race in theological innovations. If you can restate the biblical message without biblical concepts by using an undifferentiated ontology, why not try to do so by dropping even more conceptual baggage? It is no accident that the popularity of Tillich was immediately followed by the absurdity of the "God-is-dead" movement and the oxymoronic phenomenon of "secular theology." These new developments performed several important functions: a) They allowed theology to put itself into the service of political causes, such as the Civil Rights movement and the opposition to the Viet Nam war. b) They made great copy in popular media, such as Time Magazine. c) They gave wonderful opportunities for evangelicals to rail against something that required no study, and that few sensible persons would take seriously. The God-is-dead fad did not last more than a year or so, but it supplied content for sermons, rallies, and, of course, the all-important bumper stickers for many years to come.

At the same time, I would suggest that evangelical theology was undergoing some strong positive growth, qualitatively speaking. I realize that this may not be the interpretation that Mark Noll or others may be giving to this time period, but look at what happened. There was a strong rise in interdenominational and nondenominational cooperation on various levels including such items as:

At the same time, I would suggest that evangelical theology was undergoing some strong positive growth, qualitatively speaking. I realize that this may not be the interpretation that Mark Noll or others may be giving to this time period, but look at what happened. There was a strong rise in interdenominational and nondenominational cooperation on various levels including such items as:The list could go on, but it is no wonder that evangelical churches and seminaries were growing geometrically, while liberal institutions were dwindling. When I was a student at Trinity in the early seventies, we would regularly go to downtown Chicago to use the library of (the liberal) McCormick seminary. If it weren't for Trinity students, I'm afraid the library would have been totally empty on many evenings. The paradox is that the liberal groups would try to attract more students and participants by watering down their message and their standards, which only backfired. Students don't feel the need to spend three years of their lives to go to seminary where the curriculum is warmed-over sociology; people don't go to church to have the newspaper editorial page repeated to them from the pulpit; theology without an intelligible message is doomed to oblivion. (Do you hear me, emergent-churchers?)

Consequently, if it hadn't been for process theology, American non-evangelical theology would have been nothing but the stuff of comic books. At the same time some exciting developments were occurring in Germany and in Latin America, and Catholic theologians were becoming creative without giving away all content.

Well, I did it now. I didn't intend to, but I think I've accidentally gotten myself into starting a series here that's going to take quite a while to get through. I'd appreciate hearing if there's real interest in hearing more about the story of theology of the last few decades. I have a lot to share with you if there is.

| Consequently, if it hadn't been for process theology, American non-evangelical theology would have been nothing but the stuff of comic books. |

So, what is that wonderful process theology which I am apparently giving an exception? Well, I'm only making a differentiation on the basis of rigor and metaphysical seriousness. Other than that it, too, was playing the game of secularity, perhaps even better than some of the other theologies, because it tried to do so with an underpinning that was not mere jargon.Two of the best-known protagonist of this theology were Schubert Ogden (Perkins, Chicago) and John Cobb (Berkeley). Both of them started out with the notion that biblical theology was passé. Early in his career Ogden wrote a book entitled Christ Without Myth (1961), in which he asserted that Bultmann had not gone far enough in his process of demythologization because he was still maintaining elements of the Christ-myth. We need to rid our theology of anything mythological and supernatural because contemporary people are completely secular. Similarly, Cobb began his book, God and the World (1969) by accusing the God of the Bible of being the chief antagonist to human fulfillment. So, if you're thinking of the biblical God, we can do without him. However, in 1966 Ogden came out with another book, The Reality of God, in which he argued that, even though the traditional, biblical God is irrelevant, we can be helped by accepting the process God, as advocated by Alfred North Whitehead in his Process and Reality (1929). Ogden borrowed an argument from Stephen Toulmin to the effect that the basis of a moral system cannot come from the moral system itself, but from outside of it. This fact comes out in "limiting situations," occasions at which the whole notion of whether to be moral at all is brought into question. It is at this point, Ogden asserted, that we need God as a source of values, not the domineering dictator of the Bible, but the ever-accommodating God of Process philosophy. Cobb and a number of other writers, such as David Ray Griffen, Norman Pittenger, and Charles Hartshorne agreed in principle.The God of process theology is thus a God who respects human autonomy and freedom. He does not force anyone to do anything, but he gives us the values by which he would like us to live. There are three fundamental principles:

by which he would like us to live. There are three fundamental principles:

So, what did process theology achieve? This much (and I will let you decide whether it's a significant contribution or not in its own world): it provided a philosophical underpinning for the secularism and dismissal of biblically-based theology, and it underwrote thereby the ideas of human autonomy. And all it had to pay for this achievement was to settle on a god who is finite and unable to act in the world himself. The god of process theology is a sad entity who would get us to change if only we would listen to him. He did not create the world, but he exists alongside it in mutual interdependence as time moves on. There is no end point for either God and the world, but the process will continue on and on and on and on. Despite our refusal to accept his values consistently, he continues to plod away and with his third ("superjective") nature rejoices when things go his way and weeps when they don't.

One other point. Regardless of what you make of the theology presented here, there appears to be a metaphysical impossibility. Potential cannot actualize themselves, but it takes a cause to turn a potential into something actual. But note that in the scheme as I have represented it, this fact is ignored. The world's potential pole actualizes itself. God's primordial nature turns itself into his consequent nature. Thus, either there is a hidden cause somewhere after all, or process theology asserts something contrary to all of our knowledge and experience: self-actualizing potentials.Process theology stood apart from other theologies derived in the English-speaking world of the 1960's and early 1970's by demanding a rigor that went beyond sloganeering and bald assertions. Other serious attempts at meaningful (non-evangelical) theology came out of the lecture halls and printing presses of the German universities.

| Consequently, if it hadn't been for process theology, American non-evangelical theology would have been nothing but the stuff of comic books." |

At least that's how it appeared in broad strokes to some of us in the early seventies. Theologians at major denominational seminaries were vying to become known for their particular brand of "the theology of [fill in with something, anything that will make you appear relevant]" Thus Paul Van Buren came out with his book, The Secular Meaning of the Gospel already in 1963. His contention was that in the light of the philosophy of logical positivism, Christian language had lost its meaning. Logical Positivism, you will know if you have studied philosophy, applied the verifiability criterion to all language and asserted that: A statement is meaningful only if it is in principle capable of empirical verification. Thereby these philosophers ruled out all moral, aesthetic, ethical, metaphysical, religious, and theological discourse as meaningless "non-sense"; important nonsense, perhaps, but without concrete meaning. Eventually, they had to face up to the fact that the verification principle itself did not pass its own test, and the movement eventually dithered out, but that's another story. Still, right around the time that logical positivism was losing whatever grip it should never have had, Van Buren wrote his book, as a theologian, informing the church that we could no longer speak meaningfully to the world. He was usually listed among the "God-Is-Dead" theologians, but his point was not that God was dead, but that the word "God" was dead because it was no longer meaningful.

1963 happened to be the year I came to the United States. We joined a church, worshiped God, studied the Bible, and lived a Christian life, as many other people around us did as well. Nobody told us that the word "God" had become irrelevant--mostly because nobody knew that it had. I dare say that it hadn't. It was not until I ran across logical positivism in academic philosophy that I was suddenly confronted with the fact that someone had decreed that one of the most relevant aspects of our lives was actually culturally irrelevant.

Wait! Let me rephrase that. I learned that it had been irrelevant due to logical positivism, but now, in the early seventies, logical positivism was definitely out, and Wittgenstein was in. Wittgenstein's later philosophy clearly opposed logical positivism by working out a model according to which any sort of language has meaning based on the function that it performs within its context. Thus, words and sentences do not have intrinsic meaning, but within a "form of life" (a subculture, so to speak) people play "language games" (not a pejorative term) which are meaningful within that context. Therefore, to speak meaningfully is to use an expression successfully according to the expected convention of that form of life. Thus, religious language is meaningful for those who live within a religious form of life and use language as people in that setting do when they communicate with each other. And--wouldn't you know it?--in 1972 Van Buren came out with another book, called Edges of Language, in which he now dogmatically advocated applying Wittgenstein's principles of language to theology.

Now you see that the theologians' quest for relevance was extremely paradoxical. Relevance not only trumped other considerations, but it also constituted a relevance to something, which actually was utterly irrelevant to most people at the time. As much as Wittgenstein was being lionized in professional philosophical circles at the time, he was not someone whose language game too many people outside of that form of life were playing.

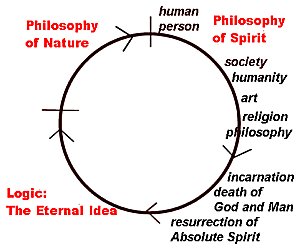

In the meantime, Thomas J. J. Altizer had made big news with his announcement that "God is dead." He came to this discovery from a very different direction than Van Buren as well as than what many people thought. Most people have come to associate the expression that "God is dead" with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, but Nietzsche's use of the phrase is really only a small part of what Altizer was advocating when he wrote God is Dead: The Gospel of Christian Atheism. For Nietzsche, the phrase was an assertion of atheism, or--to be more specific--an assertion of the the barrier that God imposed on human moral liberation, but again that's another story. To find a reference point for Altizer's meaning we have to go much further back than Nietzsche, namely to Hegel. Hegel's philosophical system, which has three major parts, hinges on the incarnation of God in Christ. It consists of his logic, the first part, in which we see "the Eternal Idea" [God] as it was before creation." But God did create, and so the second part of Hegel's system is the philosophy of nature, an analysis of the physical world. But then spirit and nature come together, and they do so first of all in human beings. Thus in the third part of Hegel's system, the Philosophy of Spirit, we move from the individual person (a "man") to humanity ("Man"). Now, here is the crucial question: in the incarnation did God join himself to "a man" or to "Man"? For Hegel the answer is the latter. Christ was not just God and a man, but he was God and Humanity combined. And then he died. So, what happened at Calvary on what Hegel calls "the speculative Good Friday" was that God died on the cross, and simultaneously Man died on the cross. But, for Hegel, then there was a resurrection; namely that as a consequence of the death of both God and Man we attain Absolute Spirit, which is pure self-conscious consciousness, or the Eternal Idea before creation, and the system starts all over again/

In the meantime, Thomas J. J. Altizer had made big news with his announcement that "God is dead." He came to this discovery from a very different direction than Van Buren as well as than what many people thought. Most people have come to associate the expression that "God is dead" with the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, but Nietzsche's use of the phrase is really only a small part of what Altizer was advocating when he wrote God is Dead: The Gospel of Christian Atheism. For Nietzsche, the phrase was an assertion of atheism, or--to be more specific--an assertion of the the barrier that God imposed on human moral liberation, but again that's another story. To find a reference point for Altizer's meaning we have to go much further back than Nietzsche, namely to Hegel. Hegel's philosophical system, which has three major parts, hinges on the incarnation of God in Christ. It consists of his logic, the first part, in which we see "the Eternal Idea" [God] as it was before creation." But God did create, and so the second part of Hegel's system is the philosophy of nature, an analysis of the physical world. But then spirit and nature come together, and they do so first of all in human beings. Thus in the third part of Hegel's system, the Philosophy of Spirit, we move from the individual person (a "man") to humanity ("Man"). Now, here is the crucial question: in the incarnation did God join himself to "a man" or to "Man"? For Hegel the answer is the latter. Christ was not just God and a man, but he was God and Humanity combined. And then he died. So, what happened at Calvary on what Hegel calls "the speculative Good Friday" was that God died on the cross, and simultaneously Man died on the cross. But, for Hegel, then there was a resurrection; namely that as a consequence of the death of both God and Man we attain Absolute Spirit, which is pure self-conscious consciousness, or the Eternal Idea before creation, and the system starts all over again/

To whatever extent you were able to follow that quick description, the crucial part is this: God died on the cross. (We will return to this notion in a while when we mention Ernst Bloch.) What Altizer had in common with Nietzsche was that the death of God issued in human liberation, though not from moral responsibility, but rather toward moral responsibility. Since God has died in Christ, it is now up to us humans to look out for the world and for each other.

Well, these were two of the popular stars in theology in the 1960s. Similar to the way the author of Hebrews closed chapter 11, I feel that I should say that I could add so much more. The bottom line seemed to be that, whatever gimmick one used, the end result was the notion that if we didn't make this a better world, nobody would because God couldn't chip in and do his part, either because he had died or was irrelevant.

However, process theology was attempting to provide humans with all the responsibility they wanted, but still leave room for God, and that's where we shall pick up next time.

Meanwhile in Germany something new was brewing in the world of (non-evangelical) theology. Germany, of course, had a lot to deal with after World War II. On the one hand, there was the matter of overcoming the Nazi era. On the other hand, there was the reality of the country being divided between East and West--Communist and Capitalist--and the war of the ideologies associated with the split.

Let me put in a quick recommendation from the conservative theological side: Helmut Thielicke held up the banner of biblically-based theology even throughout the Nazi era, and his systematic theology (The Evangelical Faith, 3 vols.) and extensive work on ethics (Theological Ethics, 3 vols.) are worthwhile both for their content per se and for the glimpses they provide of German self-reflection in the 1950's.

However, in this series we are focusing mainly on the so-called liberal side of things. Here a whole new set of dynamics came to the forefront, partially thanks to the work of a philosopher named Ernst Bloch. He was born in Germany, went into exile due to his Jewish background during the Nazi time, and when he returned to Germany, chose to settle in the East, the so-called German Democratic Republic, because he was a Communist. However, many of his views did not strictly coincide with orthodox Communism, and so his life in East Germany was not easy. Still, h was allowed to go on temporary leave from his country from time to time in order to hold lectures, and he happened to be in West Germany on the weekend when the Eastern regime built the Berlin wall. At that point Bloch decided that he would remain in the West rather than return to a worker's paradise that needed to go to extreme lengths in order to keep its citizens from escaping to other countries.

However, in this series we are focusing mainly on the so-called liberal side of things. Here a whole new set of dynamics came to the forefront, partially thanks to the work of a philosopher named Ernst Bloch. He was born in Germany, went into exile due to his Jewish background during the Nazi time, and when he returned to Germany, chose to settle in the East, the so-called German Democratic Republic, because he was a Communist. However, many of his views did not strictly coincide with orthodox Communism, and so his life in East Germany was not easy. Still, h was allowed to go on temporary leave from his country from time to time in order to hold lectures, and he happened to be in West Germany on the weekend when the Eastern regime built the Berlin wall. At that point Bloch decided that he would remain in the West rather than return to a worker's paradise that needed to go to extreme lengths in order to keep its citizens from escaping to other countries.

Bloch did not abdicate his Marxism, however. He remained a Communist, but unlike any other Communist you are ever likely to encounter. He did not think that Communism demanded the abandonment of all previously-held concepts. Even religion and mythology could make a positive contribution. He drew on his kabalistic Jewish heritage to support the notion that human beings are not just material entities. He used the Hegelian idea of the death of God in Christ to show that the fate of the world now lies in our hands. (On this point the undocumented resemblance between Bloch and Altizer is uncanny.) Thus, even though he was an atheist, he was an atheist with a lot of appreciation for religion, particularly Christianity. Most importantly, the bottom line of his philosophy was the expectation of a utopia. By this term he did not particularly mean the full mechanical implementation of Communism--from each according to their ability to each according to their need--but a state of perfection that would be so wonderful that it was at present indescribable.

As Bloch tells us in his most important piece of writing, The Principle of Hope, what drives us on as human beings is the expectation of such a utopia. We do not yet know what it will be like, but we live in the unswerving hope that it will come. Thus the central attribute of us human beings is that we always live in hope. The solution is just around the corner. We cannot now say what that solution will be because we cannot know the future, but we know that it is coming, and that it will be good beyond all words and concepts. When Bloch was once asked if he could state his philosophy in one sentence, he rose to the occasion and declared that

S is not yet P.

He could not say that S is P in the present tense because the future is not yet here. But neither is it true simply that S isnot P because we do not live in a permanently settled state of affairs. The key lies in the little word "yet." S will becomeP, and thus we can always live with the hope that things will be set right in the future. In the meantime, we can live joyfully in the light of this future expectation.

You can undoubtedly see how handily Bloch's philosophy would be able to be implemented by theologians. At the forefront of this attempt was Jürgen Moltmann, the next theologian on our agenda.

We are continuing with an overview of (non-evangelical) theology after the great luminaries--Barth, Bultmann, Tillich--started to fade. As I mentioned, in the United States there was a rash of utterly exaggerated attempts at whittling away everything substantive. In Germany, where on the whole reflective thought tends to be a little more respected than brash headlines, theologians were trying to be more rigorous in their efforts. The existential adaptations would carry things only so far. So, you find yourself; you discover the authenticity of your being; you recognize your existence; what does that get you? Simplistic humanistic solutions rely on optimism, but they cannot provide hope.

We are continuing with an overview of (non-evangelical) theology after the great luminaries--Barth, Bultmann, Tillich--started to fade. As I mentioned, in the United States there was a rash of utterly exaggerated attempts at whittling away everything substantive. In Germany, where on the whole reflective thought tends to be a little more respected than brash headlines, theologians were trying to be more rigorous in their efforts. The existential adaptations would carry things only so far. So, you find yourself; you discover the authenticity of your being; you recognize your existence; what does that get you? Simplistic humanistic solutions rely on optimism, but they cannot provide hope.

As we saw last time, an idiosyncratic Communist wound up triggering some new thoughts in Christian theology. Ernst Bloch suggested that it is the phenomenon of hope that makes us human beings. We live in a constant state of expectation; utopia is just around the corner. S is not yet P, but it will be.

Jürgen Moltmann was a young theologian, trained in a neo-orthodox environment. His earlier writings focused on Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the question of retaining a godly conscience in challenging circumstances. Coming upon the writings of Ernst Bloch helped him to establish a new way of looking at the Bible and Christian doctrine. After all, Christianity is all about looking to the future for hope. Up until then, Moltmann maintained, eschatology was only a set of doctrines scotch-taped onto the more central aspects of theology. In his groundbreaking book, Theology of Hope (1965), Moltmann said that expectations for the future are the center of theology. Whenever God interacts with human beings it is on the basis of his promise for a better future. Christians live in the expectation of the second coming of Christ, the parousia. The resurrection gives us the assurance that this hope is not in vain.

Moltmann provided seven implications of God's promise:

From the very beginnings of the people of Israel, pivoting on Christ's death and resurrection, right into the church of today, we ought to live in the spirit of hope for the impending future.

Moltmann's work was one of several that had a tremendous impact on theology. Who would want to turn down hope for the future? But by now some of my most astute readers (roughly the top ninety-nine percent) will have started to be bothered by something. Yesterday, in connection with Bloch's utopia I said that this utopia would be a state of perfection that would be so wonderful that it was at present indescribable. Utopia is coming, but we don't know what it will be like. The same ambiguity attends Moltmann's description of the future. It's coming, but we don't know yet what it will be. We cannot take biblical predictions literally or tie our hope to anything we can know with direct words or concepts, or, at least, that's what Moltmann wants us to believe.

In my first year at Trinity I took a course in contemporary theology with Dr. Carl Henry, and I did my paper on Moltmann. I remember several things in connection with it, like asking for and getting an extension on the paper due to a bad headache, but mostly that I remarked to Dr. Henry that I found Moltmann to be annoying because he was advocating hope, but the hope he was selling was hope without content. Dr. Henry reacted by saying something like, "So, Moltmann annoyed you, did he?" Annoyances can increase in degree, and there is more than one way of being annoyed.

Wednesday, May 13th 2009

I haven't talked much about any personal events of the last few days. This is the case because nothing much has happened. I'm spending every day working on some of the writing I need to do, though at a very slow pace, as well as developing more self-contained presentations, of which the most enjoyable part continues to be producing background music. So, let's go on with our series of developments in (non-evangelical) theology after Tillich.

There was a time when Jürgen Moltmann and Wolfhart Pannenberg were almost always mentioned together. The fact is that they have some things in common, but there is also a lot that holds them apart. What they share is doing theology in the light of the future. What keeps them apart is a fundamental difference in methodology.

There was a time when Jürgen Moltmann and Wolfhart Pannenberg were almost always mentioned together. The fact is that they have some things in common, but there is also a lot that holds them apart. What they share is doing theology in the light of the future. What keeps them apart is a fundamental difference in methodology.

Remember that I mentioned yesterday that Moltmann was catalyzed into the direction of his theology by the philosopher Ernst Bloch. Pannenberg read Bloch, too, but only after he had already set his own theology in motion. Moltmann mentioned to him, "you should read this," and he did, but Bloch was not his inspiration.

Neither--contrary to a very popular myth--was Hegel, even though it's hard to find a source that doesn't link the two, including, say, the Wikipedia. I've had the opportunity to talk about the matter with Prof. Pannenberg, and he outright denied that he either had a particular interest in Hegel or that Hegel had influenced him. In fact, when I initially asked him about it in a seminar-like meeting, he gave me the same lecture that I had given my fellow graduate students for about a year or so, namely that Americans by and large don't understand Hegel and that our stereotypical view of his philosophy (thesis-antithesis-synthesis) is totally off-base. My friends, as you can imagine, were gleeful. Afterwards, we got to talk some more, and I got to tell him a little more about myself, and he said that he was sorry. So we got that matter straightened out, and later on over lunch he pointed to the subject of his doctoral dissertation, Duns Scotus, as his philosophical inspiration.

Pannenberg's doctorate was in philosophy, but when the opportunity came for him to teach theology he quickly had to "throw together" a habilitation thesis (to qualify for university teaching) in theology. This "hastily" produced book, Jesus-God and Man (1968 ) , turned out to be a huge hit and will probably remain the one for which he is best known. In this book he attempted to construct a Christology "from below," which means that he started with the man Jesus and then showed that this man was (is) God incarnate. Crucial to this argument is the resurrection of Christ, and Pannenberg went to great lengths to show that it was a historical event. He also calls it a mystery, but when I asked him about using that term, he explained that he had in mind the fact that ultimately the very natures of death and life are mysterious to us. He did not mean to whittle back on the historicity of the resurrection. That assertion caused a bit of consternation among the Bultmannians in the audience.

Now, the crucial term to understand Pannenberg's theology is "proleptic." That term means that something is not yet here, but we are already benefiting from it. Thus, Pannenberg argued that the Kingdom of God is not yet here, but it is already present among us proleptically, as guaranteed by the resurrection. How is this different from what Moltmann was saying?, you might ask. Pannenberg does not resort to equivocal language. In keeping with the Scotist roots to which we alluded above, the hope to which he refers has actual biblical content.

We have now looked briefly at two German theologians who, rather than emptying theology of further content, attempted to restore content by directing us to the future and its anticipatory influence on our present. While we're on German soil in the 60s and 70s, we really shouldn't return home until we have looked at the new adventures in theology on the Catholic side. When the pope calls in a theologian for some critical consultation, and he replies that unfortunately he is too busy for a trip to Rome, something pretty controversial must be happening.

Last night I stated that I wanted to take a quick glimpse over the picket fence to what was happening in Roman Catholic theology at the same time as when Protestant theology was seeing its way past Tillich and Barth. After thinking about this for almost a whole day, I decided that I really needed to clarify some of the philosophical background that moved Catholic theology into new realms of thought. Who was the Ernst Bloch, so to speak, on the Catholic side? Now, I'm not talking about anyone taking over for St. Thomas Aquinas in terms of providing the basic categories, but again, just as with Bloch, someone who served as catalyst, someone who provided a different perspective. In this case it was a heretic who has never been reinstated, but whose thought patterns are seen all over the documents of Vatican II: the Jesuit paleontologist, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955).

Let me clarify here that the Society of Jesus, usually called the Jesuit order, functions differently than other orders in many respects. Every member is expected to attain full priesthood and complete mastery (e.g. a doctorate) in some field, frequently outside of theology. For example, when I was an undergraduate I became acquainted with a Jesuit priest who was working on a Ph.D. in chemistry, and most of my students of the last twenty years know about Harry Gensler, S.J., the logician. So it was not unusual that Teilhard should become a highly respected paleontologist. His first field experience occurred with the unfortunate Piltdown man, but he went on from there and was a part of the teams that unveiled Sinanthropus and Pithecanthropus.

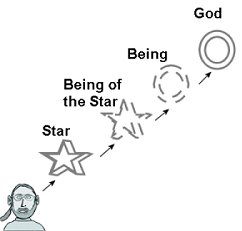

Teilhard was committed to the theory of evolution, not just of human beings or other forms of life, but of the entire universe, and he encased it in highly speculative theological interpretations. As he described in his most important book,The Phenomenon of Man (published posthumously), evolution does not occur apart from God's immediate direction. The whole cosmos is guided in its development by God, and it manifests purposiveness and anticipation of the next stage as it passes through three spheres.

Teilhard was committed to the theory of evolution, not just of human beings or other forms of life, but of the entire universe, and he encased it in highly speculative theological interpretations. As he described in his most important book,The Phenomenon of Man (published posthumously), evolution does not occur apart from God's immediate direction. The whole cosmos is guided in its development by God, and it manifests purposiveness and anticipation of the next stage as it passes through three spheres.

Let's get the critique over with. What we see here is deficient as science thanks to the notion of self-conscious evolution, as philosophy because it constitutes speculation without foundation, and as theology since, according to the church, it did not have a sufficient doctrine of original sin (though I can think of some other shortfalls as well). More importantly, what contribution could this strange eclectic make to the very church that forbade him from teaching? Teilhard provided a vision that amounted to nothing less than a paradigm shift. What didn't change was that the church saw itself as the only vehicle of salvation, but it altered the implication of that idea. It moved from a mentality of isolation and separation to a triumphalism in which the church ultimately swallows up everyone else, and all of humanity finds unity with Christ.

As I mentioned above, Teilhard has never been reinstated, and there is no reason to expect anything along that line to happen. Nevertheless, about ten years after his death, the second Vatican Council asserted in the Pastoral Constitution on the Church Today (Gaudium et Spes),

Christ is now at work in the hearts of men through the energy of His Spirit. He arouses not only a desire for the age to come, but, by that very fact, He animates, purifies, and strengthens those noble longings too by which the human family strives to make its life more human and to render the whole earth submissive to this goal.

and

For after we have obeyed the Lord, and in His Spirit nurtured on earth the values of human dignity, brotherhood, and freedom, and indeed all the good fruits of our nature and enterprise, we will find them again, but freed of stain, burnished, and transfigured. The will be so when Christ hands over to the Father a kingdom eternal and universal: "a kingdom of truth and life, of holiness and grace, of justice, love, and peace." On this earth that kingdom is already present in mystery. When the Lord returns, it will be brought into full flower.

What makes these statements distinctive is the not-so-concealed universalism under the aegis of the church, the notion that all of humanity will eventually become one in Christ. They are a tacit testimonial to the man whose name was constantly mentioned in the small sessions behind closed doors, but never out loud in the public meetings: Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

In my ongoing efforts to recover from accidentally obliterating several years' worth of blogs, I'm happy to announce that the three series, How to do Theology, Some Issues in Catholicism, and How to Do Apologetics are once again functional.

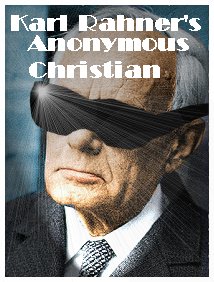

When Pope John XXIII banged his gavel, asked all of the bishops to sit down and stop chattering in Latin, warned them not to stick their gum on any other bishop's cassock*, and officially opened the second Vatican Council in 1962, the theologian whose ideas were about to be implemented on a grand scale just happened to be under censure by the church. By the time the council was done in 1965, his ideas had become the new standard of orthodoxy. The person in question was Karl Rahner, S.J. (1904-1984), who had caught the Teilhardian vision of all of humanity coming together in Christ.

When Pope John XXIII banged his gavel, asked all of the bishops to sit down and stop chattering in Latin, warned them not to stick their gum on any other bishop's cassock*, and officially opened the second Vatican Council in 1962, the theologian whose ideas were about to be implemented on a grand scale just happened to be under censure by the church. By the time the council was done in 1965, his ideas had become the new standard of orthodoxy. The person in question was Karl Rahner, S.J. (1904-1984), who had caught the Teilhardian vision of all of humanity coming together in Christ. Rahner's age and stature are more comparable to Barth and Tillich on the Protestant side than, say, Altizer or Moltmann. However the subsequent developments require a little Rahnerian pre-knowledge. Rahner was one of those rare theologians who was explicit about his philosophical presuppositions, and, consequently, he turned out to be an easy choice for your humble bloggist to write his Ph.D. dissertation on. (see my paper in the Harvard Theological Review 71 (1978 :285-298.) You see, Rahner had studied for a doctorate in philosophy, and had finished his dissertation, a study of the nature of knowledge based on Aquinas' Summa Theologica 1, q. 84, though not a traditional one. In fact, it was sufficiently non-traditional that his doctoral chair dismissed it flippantly. In that same year, Rahner proceeded to get a doctorate in theology by writing a very traditional disseration on the origin of the church in the wounds of Christ. I suspect that the theological dissertation has been available somewhere at some time, but his rejected work in philosophy, entitled Spirit in the World, has become a genuine classic.

Rahner is not easy to read because his theological German is amplified by liberal borrowing and neologisms, as warranted. The story goes around that his brother Hugo, a scholar himself, once said that one of these days he will translate his brother's works into German. So, my summary is once again going to be somewhat simplified. A crucial part of his thought is the Hegelian idea to which we took recourse several times already that in the incarnation God joined himself, not just to a man but to humanity. At the same time as God became incarnate, humanity became divinized. Thus, to devote yourself to Man (I'm choosing the word as well as the capitalization intentionally) is ultimately to devote yourself to God.

Rahner is not easy to read because his theological German is amplified by liberal borrowing and neologisms, as warranted. The story goes around that his brother Hugo, a scholar himself, once said that one of these days he will translate his brother's works into German. So, my summary is once again going to be somewhat simplified. A crucial part of his thought is the Hegelian idea to which we took recourse several times already that in the incarnation God joined himself, not just to a man but to humanity. At the same time as God became incarnate, humanity became divinized. Thus, to devote yourself to Man (I'm choosing the word as well as the capitalization intentionally) is ultimately to devote yourself to God.

More specifically, what does it mean to be human? Well, a human person is an embodied spirit who has the disposition (potentia obedientialis) to listen to God. By divine grace, human beings come with a little hook-up to God, the "supernatural existential." So, as a spiritual entity I get to know the world around me. I see what I might call "entities" or "beings," viz. things that exist. But even though my knowledge of them begins as phantasms in my mind, I also have the faculty that Rahner calls the Vorgriff (literally "pre-grasp") that penetrates past the phantasm to the being of the entity. After all, in order to be something, you first of all have to be, and vice versa. So, the fact that a thing is precedes what it is. In fact, we can take matters one step further and say that in order to know another entity, we must implicitly posit our own being and the being of the other. So, knowledge of even a simple object presupposes a direct relationship with being, simply as being.

But wait! What is "being" pure and simple? When we talk about being qua being, and not just some entity or other, we are, in fact, making reference to the only being that is pure being, and that is God. And we cannot talk about some entity or other without tacitly acknowledging being pure and simple. Therefore, whenever I exercise the part of me that makes me human, namely my ability to know things, I'm making reference to God, whether I realize it or not. And, of course, there is only one God. So, all human beings, insofar as they do not act counter to their humanity (which includes treating other people as owning the same humanity), stand in a relationship with the God of the church and the Bible. Thus, in a minimal sense, they are Christians. Needless to say, many--no: most--people are unaware of this supposed fact. Rahner calls them "anonymous" Christians.

I've pictured Rahner cleverly disguised as anonymous Christian.

*The specific details mentioned in this description are not based on historical documents, and any facticity would be purely coincidental.

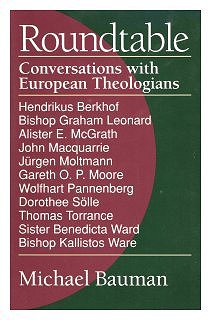

First, a book recommendation. Michael Bauman mentioned in a feedback comment the other day that he had written a book that contains interviews with Moltmann and Pannenberg among others. Obviously, I sent him an e-mail right away that I was interested in it, and Michael sent me a little care package with that book, called Roundtable, and a couple of others to which he has contributed. Thanks, Mike! The book is a great production, and the interviews with Pannenberg and Moltmann are both extremely insightful. Michael Baumann is professor of theology and culture at Hillsdale College.

First, a book recommendation. Michael Bauman mentioned in a feedback comment the other day that he had written a book that contains interviews with Moltmann and Pannenberg among others. Obviously, I sent him an e-mail right away that I was interested in it, and Michael sent me a little care package with that book, called Roundtable, and a couple of others to which he has contributed. Thanks, Mike! The book is a great production, and the interviews with Pannenberg and Moltmann are both extremely insightful. Michael Baumann is professor of theology and culture at Hillsdale College.

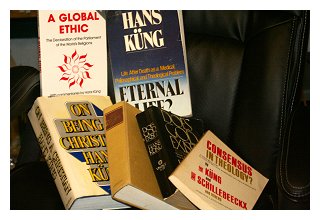

And now let me return to our theologians of the late sixties and seventies, still on the Catholic side, and say a few words about Hans Küng. By the way, that previous sentence will have been one of the very, very rare occasions that you will see the phrase "a few words" and Hans Küng's name together. His books tend to be rather sizeable tomes characterized by German thoroughness (Gründlichkeit), not because he is verbose, but because there is so much content in them. Still, they are actually easy to read.

Küng's first work attracted quite bit of attention. It was entitled Justification, and its thesis was that the Reformation rested on a gigantic misunderstanding. Using Karl Barth as his representative for Protestantism, he tried to show that both Luther and the Church overreacted, and that it never should have come to a split. This certainly was an interesting thesis, though it seems to me that it's a whole lot more plausible to let the Reformers speak for the Reformers themselves, in which case there would be an issue after all. In case you're interested, a much more realistic treatment from the Catholic side, that does not try to rationalize away important differences, can be found in Michael Schmaus's 6-volume set Dogma, particularly in the last volume, also entitled Justification.

Then Küng wrote the book that got him into hot water, out of which he has never totally emerged again. It was called Infallible? An Inquiry, and--as the name implies, he questioned the doctrine of papal infallibility. He pointed out the many times that popes had made mistakes, to put it mildly, and that the doctrine was incompatible with other Catholic beliefs. That's not a good thing for a Catholic theologian to do. The folks in Rome were stirred up and invited Küng for a visit and a chat. Küng replied that, unfortunately, he was awfully busy at the moment, and his calendar did not permit him the luxury of a trip to Italy, which did not garner him any sympathy. But there's another interesting wrinkle to this matter: many theologians believe that Küng was attacking a straw person in this book. He basically interpreted the doctrine of infallibility as implying that a pope is always right in whatever he might say around the clock. However, when papal infallibility was declared to be dogma by Vatican I (1870), they had no such absurd idea in mind. The pope is supposed to be infallible only on the condition that he speaks ex cathedra and specifically points out that he is announcing something that must be believed by all. Such an occasion has only occurred once since first Vatican council, namely in 1950, when Pope Pius XII declared the bodily assumption of Mary to be a de fide obligatory belief.

Then Küng wrote the book that got him into hot water, out of which he has never totally emerged again. It was called Infallible? An Inquiry, and--as the name implies, he questioned the doctrine of papal infallibility. He pointed out the many times that popes had made mistakes, to put it mildly, and that the doctrine was incompatible with other Catholic beliefs. That's not a good thing for a Catholic theologian to do. The folks in Rome were stirred up and invited Küng for a visit and a chat. Küng replied that, unfortunately, he was awfully busy at the moment, and his calendar did not permit him the luxury of a trip to Italy, which did not garner him any sympathy. But there's another interesting wrinkle to this matter: many theologians believe that Küng was attacking a straw person in this book. He basically interpreted the doctrine of infallibility as implying that a pope is always right in whatever he might say around the clock. However, when papal infallibility was declared to be dogma by Vatican I (1870), they had no such absurd idea in mind. The pope is supposed to be infallible only on the condition that he speaks ex cathedra and specifically points out that he is announcing something that must be believed by all. Such an occasion has only occurred once since first Vatican council, namely in 1950, when Pope Pius XII declared the bodily assumption of Mary to be a de fide obligatory belief.

Infallible? was followed by The Church, which begins with the quote, "Christ promised the kingdom of God; what we got was the Church." I don't have the book in front of me now, and I don't remember whom he was quoting. Whoever it was meant it in a positive way, indicating that the church is God's fulfillment of the promise, but Küng intentionally gave a more negative meaning to it. Christ promised the kingdom, and we have to settle for the Church. Well, that didn't win him any friends in the hierarchy. I must say, though, that this is a very insightful book. As long as you keep your salt shaker handy, you can learn quite a bit from Küng's insights in this work.

I don't know that going on with an annotated bibliography is going to keep you amused and edified, so I will try to cut it short. The tomes kept coming. Menschwerdung Gottes, a treatise on Hegel's view of the incarnation, which I'm not sure has ever been translated into English, gave way to the blockbuster On Being A Christian, followed by another huge success withDoes God Exist? Each of these books contained just enough controversial assertions to keep the hierarchy interested in conversation with Küng, but Küng refused to go and, as he put it, be catechized. He now no longer gave silly answers, but came right out and said that any inquiry would be depriving him of his freedom, and he would not be put to the question.

As a result, in 1979 the Catholic Church decreed that Hans Küng was no longer permitted to teach as representative of the Catholic Church. It did not excommunicate him or disrobe him from his priesthood. It did not even say that he could not teach; he remained on the faculty of Tübingen University as professor of ecumenical theology. However, he could not teach as a specifically Catholic theologian.

Unsurprisingly, the response from all around Christendom was a thunderous denunciation of the Roman Catholic hierarchy. Personally, I find such a response to be downright silly, reminiscent of all the criticisms levelled at the ETS for enforcing its rules for membership. As I keep saying, if you want to belong to the flat earth society, you should believe in a flat earth. If your conscience leads you to believe otherwise, you can't be in the club. It certainly was Professor Küng's right to dissent from the church or not to answer their inquiries into his doctrinal alignment with the church. But it also was the church's right to say that, in that case, he could no longer represent the church with his teaching. As a non-Catholic, I'm not sure I'm entitled to pass judgment, let alone condemn the church for passing judgment. There are plenty of real issues between us as it is.

Küng has continued to write, particularly focusing on ecumenism and interreligious dialog. For the centennial meeting of the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1993 he wrote the draft of their declaration, entitled A Global Ethic. The draft became the official version without much input from the delegates, which irritated quite a few of them, though they signed it. It's the kind of statement that on the surface is so vague that it says very little--unless you happen to believe that one ought to kill people in order to impose your values on them. However, when one reads Küng's own commentary on it, it becomes clear that there is an agenda underneath it, which I will generalize with the statement that religious conservatives (i.e. those who are closely tied to their beliefs) need to bridle their convictions so that we can achieve harmony. We are all one, as it were, except for the extremists. An extremist, of course, is someone who is not willing to put his beliefs on the table for the sake of harmony. See chapter 4 of my Tapestry of Faiths for a few more details on my reaction.

Hans Küng is adored as martyr by many, rejected by many others. I have several reactions:

The next time I come back to this series the topic will be liberation theology.

Meanwhile, in other parts of the world . . . Yeah, I should clarify that a little bit. I'm returning to the series on theology in the late sixties and seventies, having concentrated on North America and Germany. But there was also Liberation Theology.

Liberation Theology didn't necessarily have to be Latin American, Catholic, or Marxist-influenced, but for the most part it was. Furthermore, it was at least implicitly oriented towards revolution, though theoretically it would be possible to have it be non-violent as well. I think we need to be clear on the fact that if we think that, say, the American revolution was justified, and if a revolution in certain Latin American countries would actually help the oppressed poor, then a revolution there would be justifiable a forteriori.

As an example, let me use the first Liberation theologian to whom I was exposed, Juan Luis Segundo (1925-1996), who is recognized as one of the founders of the movement. He was a medical doctor who became a Jesuit and a theologian. His major work is the five-volume Theology for Artisans of a New Humanity (1973), one volume of which was entitled: Our Idea of God. His main point was that theology must be practical, and that it must be geared to freeing people who are being exploited by multi-national corporations, which are not being held accountable by anyone.

As an example, let me use the first Liberation theologian to whom I was exposed, Juan Luis Segundo (1925-1996), who is recognized as one of the founders of the movement. He was a medical doctor who became a Jesuit and a theologian. His major work is the five-volume Theology for Artisans of a New Humanity (1973), one volume of which was entitled: Our Idea of God. His main point was that theology must be practical, and that it must be geared to freeing people who are being exploited by multi-national corporations, which are not being held accountable by anyone.

So, what kind of notion of God would a Liberation theologian advocate? For example, would he be concerned with the fine points of orthodoxy that separate a correct understanding of the trinity from heretical ones? In the case of Segundo, the answer is yes; he thought that it is essential to have a theologically accurate understanding of God, and the doctrine of the trinity played an important role in his views. However, his reason for maintaining an orthodox theology is not for its own sake, but rather because only an orthodox theology provides the needed basis for political reform.

Thus, the philosophical orientation that undergirded Segundo's theology was pragmatic. He did not argue that orthodox theology is correct on independent grounds, and, therefore, we should liberate oppressed people. Rather, his case was that orthodox theology is correct because it leads us to liberate oppressed people. Take, for example, the doctrine of the trinity. There are two heretical extremes with regard to this doctrine:

In the orthodox view the three persons are each the one God, but they are eternally three and are, thus, capable of maintaining relationships with each other. Thus this doctrine demonstrates that human persons are linked to each other, but not so that the importance of each individual person may be sacrificed.

Insofar as Liberation theology has lost its impact (which is difficult for me to assess here in Smalltown, USA), this would be due to a large extent to it having been obscured by inanition. It was all-too-easy for anyone with a complaint to imitate serious theologians, such as Segundo, and to write themselves into a theology of the oppressed. At that, it seems to me that Segundo's pragmatic method, which I find intriguing because he does endorse orthodoxy, is an ex post facto ratiocination. It makes more sense to me first to derive a theology on its own ground, and then to apply it wherever it is appropriate rather than to make it appear that the political agenda actually yields an orthodox theology.

Part 1, which is not about John Howard Yoder.

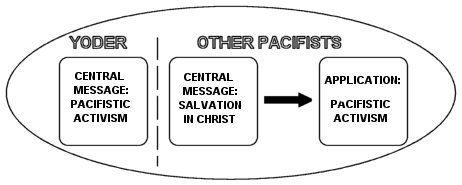

Finally I return to the series on theologians of the sixties and seventies by responding to a request to discuss one more person: the Mennonite Pacifist John Howard Yoder, who made quite an impact with his book, The Politics of Jesus(1972, revised, 1994). You can read this book on two levels. For one, you can simply use it as a source for information on Jesus' political views, as the author contends he held them. Yoder emphasized that he was not a biblical scholar per se, but an ethicist who was studying the Bible in order to reach certain conclusions about Christ's ethics and its implications for us. But even if one finds Yoder's conclusions somewhat farfetched,the book is still a valuable source of insights by taking a careful look at the assumptions that Yoder brought to his project.

Before going any further with Yoder, however, I need to provide a much broader historical setting, going all the way back to the early nineteenth century.

The nineteenth century was dominated by an anti-supernaturalist ideology. David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874) set off the starter's gun for the race to uncover the identity of the true historical Jesus. Now, if you're new to the theological world, you may wonder why one can't take Jesus' identity, as it is described in the gospels,, at face value. The answer is that the evangelists portrayed Jesus as the Son of God, a supernatural person if there ever was one. He came into this life by means of a virgin birth, performed miracles, and even was resurrected. An increasing number of philosophers and theologians rejected any such supernaturalism. Miracles, particularly such spectacular ones as a virgin birth and resurrection just don't happen, so the gospel's description of Jesus cannot be historical. Thus, the quest for the historical Jesus was actually the quest for the non-supernatural Jesus.

In 1820 Thomas Jefferson completed the so-called Jefferson Bible, a collation of the gospels with all of the supernatural events and attributes of Jesus eliminated because he thought that removing all of the material that required "superstition" would make Christianity more appealing to Native Americans. But the Jefferson Bible is a good example for the point I'm trying to make. Without all of the supernatural aspects, the gospels are empty, cliche-filled homilies that lack all motivation for why Jesus would be arrested and executed, even if he wasn't resurrected Why would people be so angry at him when all he did was to teach everyone to love each other?

Thus, the quest for the historical Jesus was extremely tricky. It would not do just to declare him to have been a completely ordinary human being because completely ordinary human beings don't get crucified, and people don't claim about ordinary human beings that they are the resurrected Sons of God. The well-prepared questor not only needed to de-supernaturalize Jesus, he also needed to substitute something that would make Jesus almost as interesting, and that would make sense of the events of his life

The easiest way to go was to turn the teachings of Jesus, and thereby Christianity, into a system of morality. A leading thinker along that line was Albrecht Ritschl (1822-1889), who reinterpreted all Christian doctrines into various concepts of relationships and the moral obligations tht they carry with them. In the United States, Ritschl's fairly abstract moral idealism was turned into the social gospel under the leadership of Walter Rauschenbusch (1861-1918 ) .

We can call this theology-as-ethics "classic liberalism," and it died rather dramatically with World War I. But anti-supernaturalism did not.

We'll have to pick up the story from here next time.

Part 2, in which Yoder does not appear at all.

We left off last night with the demise of classic liberalism thanks to World War I (not that it hasn't attempted to rear its head again and again ever since). It was survived by its progenitor "anti-supernaturalism" and its young infant brother "neo-orthodoxy." Barth, Bultmann, Brunner, Tillich (with whom we began this whole story), each in their unique ways, attempted to give us a theology that did more than encourage us to be better people, but each one also bought into the negative criticism of the Bible. Of the four scholars mentioned, it is Rudolf Bultmann, of course, who is most famous for his intentional demythologization. The others dymythologized informally as they went along. Whatever they were teaching us for our day, it did not involve a universe in which angels and demons were real beings, and in which miracles happened.

But wait! Doesn't the story of Christ specifically involve supernatural beings? Look at these passages (all of them from the HCSB):

John 12:31: Now is the judgment of this world. Now the ruler of this world will be cast out.

Eph. 6:10-13: Finally, be strengthened by the Lord and by His vast strength. Put on the full armor of God so that you can stand against the tactics of the Devil. For our battle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the world powers of this darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavens. This is why you must take up the full armor of God, so that you may be able to resist in the evil day, and having prepared everything, to take your stand.

Eph. 3:10: This is so that God's multi-faceted wisdom may now be made known through the church to the rulers and authorities in the heavens

Under an anti-supernatural agenda, verses such as these simply cannot mean anything. Or can they?

Enter Hendrikus Berkhof.

This is the entire entry on this theologian in the Theopedia, a theologically-oriented replication of the Wikipedia.

Hendrikus Berkhof (1914-1995) was a theologian in the Dutch Reformed church. After receiving his B.D. and Th.D. degrees at the University of Leiden, Berkhof served as a minister for twelve years, as Principal of the Theological Seminary of the Netherlands Reformed Church from 1950-1960 and many years as Professor of Dogmatics and Biblical Theology at the University of Leiden. |

Berkhof was critical of the traditional view of Scripture and denied both inerrancy and the infallibility of the Bible. He viewed the virgin birth as a myth and ultimately denied the incarnation, deity of Christ, and the Trinity. In Berkhof's words, "The New Testament shows us a history in which the man Jesus, because of his total obedience even to death, may share in the life and rule of God." |

[This article is a stub. Please edit it to add information.] |

Publications |

* Christ and the Powers. Herald Press, 1977. |

* Christian Faith: An Introduction to the Study of the Faith. Eerdmans, 1979. |

* Introduction to the Study of Dogmatics. Eerdmans, 1985. |

* Two Hundred Years of Theology: Report of a Personal Journey. Eerdmans, 1993. |

* Christ the Meaning of History. Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2004. (reprint) |

The Wikipedia article is even shorter. Not that this makes any difference per se. Your faithful bloggist does not even have a Wikipedia article. (He did once, but it was removed on grounds of an alleged lack of significance.) My point is simply that Professor Berkhof appears to have had a rather "normal" career as scholar/teacher, including the solid output of five books. (I have to add that I am as curious as anyone about the fourth title on this list. The dates for his birth and death do not add up to two centuries. If anyone has access to that work, I would appreciate a clarification.)

So, this fairly successful, though not outstanding, theologian wrote five books that probably don't say much to most of those who are reading this blog, given his theological presuppositions. However, there is one aspect of his teaching--that even predates these five books-- which has received a massive acceptance irrespective of its context or implied assumptions, namely his take on the "principalities and powers." I have seen numerous references to Hendikus Berkhof's work and have heard many people invoke him in oral presentations or conversations, and it is always on this one point and nothing else: the various passages dealing with the principalities and powers are not about supernatural beings, but are actually about human governments. Or, if we want to be a little more precise, they are about the governmental institutions and power structures of the present world. Berkhof argued that these structures ought to be subordinate to Christ, and, insofar as they are not, Christ is leading them to eventual subordination to the kingdom of God.

Given the problem with which we began this discussion, you can see the benefits of Berkhof's contribution:

To put it another way, Berkhof made it possible not only to accept the words of Jesus and of Paul, but to accept them at face value without having to purge them of supernatural mythology since, according to him, they never were about supernatural mythology but about political reality..

Please note that I have not given you Hendrikus Berkhof's exegetical argument for taking this interpretation; as always, things are going slowly enough as they are, and I am primarily trying to trace a historical line. Nor am I going to give you a solid counter-argument other than to register my dissent on the basis that one has to give away an awful lot of surrounding content in order to make them come out out this way. However, to many theologians, Berkhof's conclusion appeared like a voice from heaven. I'm in no position to judge that these scholars received Berkhof's views uncritically, but they certainly accepted them immediately as something that had been lacking heretofore. Berkhof had opened a new door that made it possible, if not obligatory, for Christianity to concern itself with political structures.

One of the people deeply affected by Hendrikus Berkhof's work was John Howard Yoder.

I got to hear John Howard Yoder speak once, and I was quite impressed by him. It was at the 1984 meeting of the Society of Christian philosophers at Notre Dame. His presentation was as much pastoral as it was academic. He clearly demonstrated a sharp intellect, fluent delivery, and just the right touch of stage appeal with his Amish suspenders over a white shirt (a little bit like Castro in fatigues with a cigar or, for that matter, I guess, like Corduan wearing a kurta). He did not use the occasion to make a case for pacifism as everyone probably expected. He smiled slyly and said that he knew his chances of converting everyone present to pacifism were rather low, so instead he exhorted us to remain rigorously faithful to whatever "just-war" theories we were paying allegiance to. He made the contrast between the use of limited force, as most of us would probably consider it to be justified, and a statement by the post-World War II Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who appeared to be advocating a "get-them-before-they-get-you-and-stomp-them-into-the-ground" aggressive preemptive warfare.* To understand this scenario, you must realize that Yoder was at this time an extremely well known individual, and everyone knew his main message inside and out, so there could be no question of his compromising his position; he was casting his net to reach those whom he could touch with a partial message, though not in all likelihood with the entirety of it.

I got to hear John Howard Yoder speak once, and I was quite impressed by him. It was at the 1984 meeting of the Society of Christian philosophers at Notre Dame. His presentation was as much pastoral as it was academic. He clearly demonstrated a sharp intellect, fluent delivery, and just the right touch of stage appeal with his Amish suspenders over a white shirt (a little bit like Castro in fatigues with a cigar or, for that matter, I guess, like Corduan wearing a kurta). He did not use the occasion to make a case for pacifism as everyone probably expected. He smiled slyly and said that he knew his chances of converting everyone present to pacifism were rather low, so instead he exhorted us to remain rigorously faithful to whatever "just-war" theories we were paying allegiance to. He made the contrast between the use of limited force, as most of us would probably consider it to be justified, and a statement by the post-World War II Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who appeared to be advocating a "get-them-before-they-get-you-and-stomp-them-into-the-ground" aggressive preemptive warfare.* To understand this scenario, you must realize that Yoder was at this time an extremely well known individual, and everyone knew his main message inside and out, so there could be no question of his compromising his position; he was casting his net to reach those whom he could touch with a partial message, though not in all likelihood with the entirety of it.The message, based on his book The Politics of Jesus (1972, rev. 1994), with which presumably everyone at that convention was familiar, was that at the core of Jesus' teaching was the creation of an utterly consistent pacifistic community. You may have, as I have many times, heard people say that the Jews expected a political messiah, but that instead Jesus came as a "spiritual" messiah. Instead of taking over the world, he died for the world (and was resurrected and taken to heaven, from where he will return). Yoder wants to have none of that. According to his reading, Jesus did, indeed, come as a political messiah with a political message that challenged the political structures of the world.

It is here that we need to make use of the background material I have attempted to provide over the last couple of postings. Yoder, though not technically a scholar in biblical studies, but an ethicist studying the Bible, identified with a method of interpretation called "biblical realism." As is the case with many theological phrases, this one does not mean exactly what one would think, taking it literally. "Biblical realism" is not biblical inerrancy or infallibility; it is a post-liberal way of approaching scripture as self-contained literature, advocated by such writers as Markus Barth, and closely allied to the narrative approach of Hans Frei. (If this is coming a little fast at you, and you would like to see it sorted out just a little more, please see my article published a couple of years ago by Knowing and Doing.). "Realism" here means that one accepts pretty much what the Bible says as it says it as a part of its content, just as one would accept, say, what Hamlet says in the play named after him, but--again similar to Hamlet--one does not get hung up on issues of historical precision or accuracy. The long-and-short of it is that we see Yoder in this book

Let me attempt to give you a summary of Yoder's take on the message of Jesus in his own words, with just the syntax changed a little. (The Politics of Jesus, 1994, p. 96) Jesus was

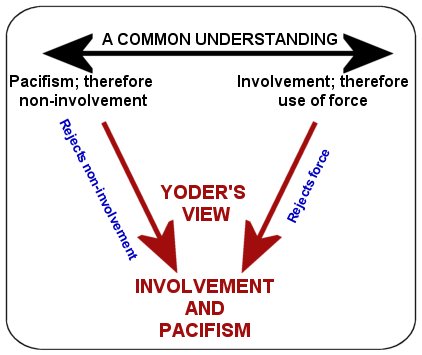

I made the accompanying chart in order to clarify what Yoder is saying. Traditionally, it seems as though there are only two alternatives regarding a Christian's involvement in world affairs. He or she can be pacifist, which also is taken to imply quietism, viz. not actually getting involved in any political issues. Thus, such a quietist-pacifist Christian might recognize the many injustices in the world, but do nothing other than to wait for God to fix the problems. On the other hand, the Christian can be involved in the struggles of the world; but that commitment is most likely going to lead someone sooner or later to use of force and violence.

However, in Yoder's interpretation of the teachings of Jesus, these two options represent a false dilemma. According to Yoder, Jesus was founding a new community that went totally against conventional wisdom. This community would be actively involved in promoting social values and, thereby, both directly and indirectly simultaneously challenging the existing power structures. But the community would be utterly and completely pacifistic, thereby going even further in showing up the repressiveness of those in authority. Thus, Yoder is able to advance a plausible answer to the question of why the authorities were so outraged at Jesus to the point of having him be crucified. He was at one and the same time exposing the evil of the present structures for all it was, but due to his total pacifism, he deprived them of the possibility of legitimate retalliation. They hated him for what he stood for, and then they hated him even more because they couldn't find anything in him to hate him for, so, eventually, they just let their hate take over and kill him.